Yes, we are building more – but not the right type of homes

On the face of it, little appears to have changed in many of the figures in this Daft.ie House Price Report. Sale prices – whether measured by listed prices or using the Property Price Register – are up compared to three or 12 months ago.

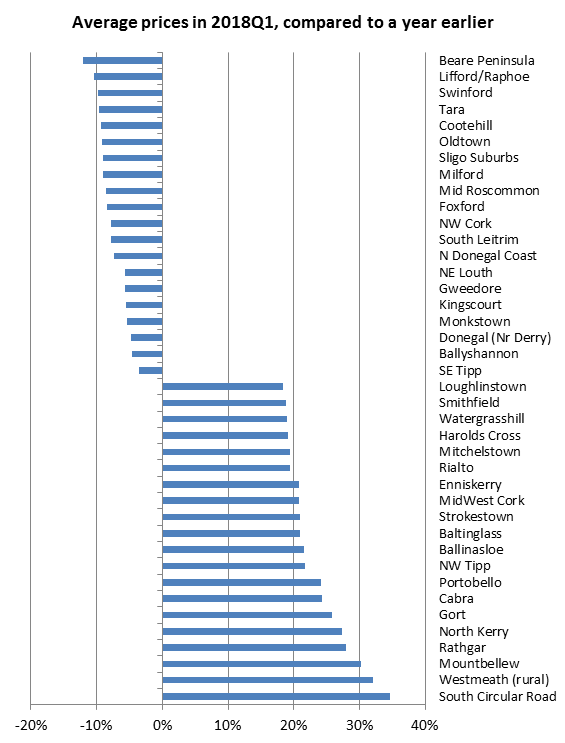

And that’s true for pretty much everywhere in the country – Donegal once again the exception, as Brexit continues to kill confidence in much of the market there. Yet another quarter of rising prices is to be expected in a market characterised by strong demand but very weak supply of new homes.

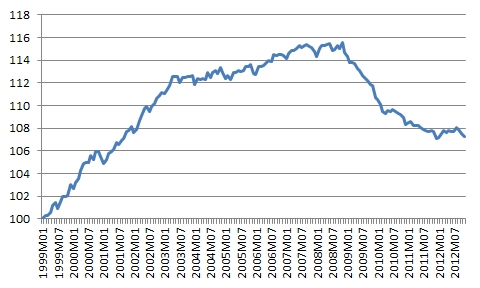

Scratch a little bit beneath the surface and there are hints that the picture is slowly changing. Compared to a year ago, prices are just 5.6pc higher. Granted, this is well ahead of inflation, which is – give or take – zero. But 5.6pc is the lowest rate of inflation we’ve seen nationally in over four years, since the first quarter of 2014. And that was when inflation was on the way up, not the way down. The quarter before this, late 2013, annual inflation was 0.3pc and three months later it was 9.8pc.

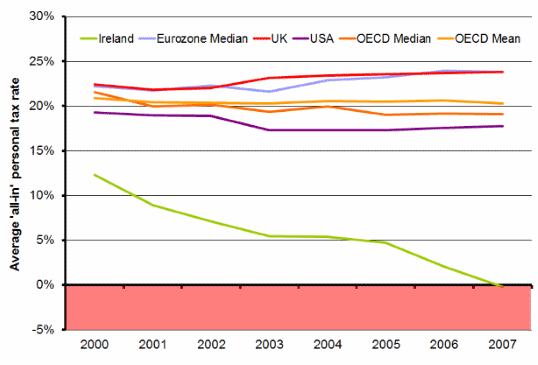

The last time we saw a similar set of circumstances – inflation close to 5pc and falling – was actually over a decade ago, in the middle of 2007.

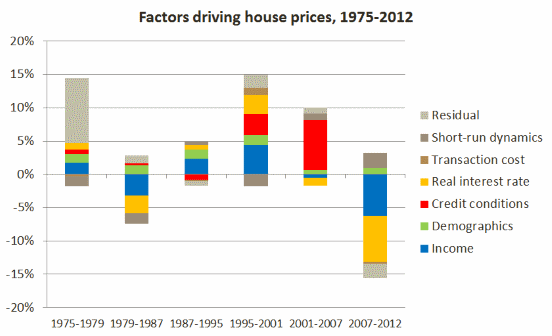

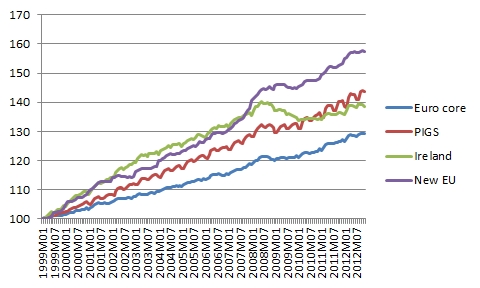

We know what happened next then. By the end of 2007, prices were falling and fell dramatically over the coming five years. This was due to a credit bubble collapsing, with both real and financial economic shocks hitting the housing market – including higher unemployment and higher deposits required by banks.

This time around, almost no one expects anything similar to the 55pc fall in prices we saw then. This is because Central Bank rules have dramatically reduced the potential impact of the most volatile parts of the house price equation. These are the so-called “asset factors”: expected capital gains and loose lending standards.

So what might be causing this slow-down in inflation? And can we expect it to continue? With asset factors no longer able to drive house prices changes, this means that the forces pushing prices up or down become more ordinary: supply and demand.

And the picture that is emerging – in the sales segment at least; no such trend has yet emerged in the rental segment – is that supply is slowly but surely coming on stream. The total stock available for sale in Dublin in June was just shy of 4,800. Together with the same time of year in 2015, this is the highest availability has been since prices bottomed out.

Outside Dublin, the shoots are even greener. The total number of homes available to buy on the market, excluding Dublin, reached a low of 16,800 in March this year – down from a high of almost 57,000 in mid-2009. There has been a jump in availability in the last three months, 16,800 to 18,800. But it is too early to tell if that is just seasonal or the start of a trend.

For Dublin, though, the increase in availability matches the increase in construction activity. Newly available – and accurate – housing completion figures show that 15,200 homes were finished in the 12 months to March. This is more than three times the number of homes completed during 2014.

While this is still well below the 40,000 or so new homes the country needs, that total includes all types of homes, including social and rental. The private sales market is inching closer to producing the number of new homes it needs each year, though, and this is likely to be seen in more moderate price increases in the coming years.

While one-offs still make up almost one-third of new homes, the majority of new homes built currently are in housing estates. Some 56pc of new homes now fall into this category – with just 15pc of new homes coming in apartments.

There are three big-picture trends that are expected to define housing demand in Ireland over the course of the 21st Century: growth in the population, especially over the age of 50; urbanisation; and falling household size. All these three point inevitably to a huge need for urban apartments, not houses.

So, the challenge for the country is that almost all the net new housing need over coming decades will be in the form of urban apartments.

But the vast majority of what is being built is not apartments. There is nothing wrong with scheme houses as an interim solution, while the policy system figures out how to fix apartment-building – as long as policymakers know that this is what is happening.

==

Versions of this post were published in the Sunday Independent and in the 2018Q2 Daft.ie House Price Report.