Another fine mess! So you want to value some properties…

Dear Government,

Well, you can’t say you weren’t warned. Yes, it was a noisy time for all concerned, with plenty of people telling you they didn’t want to pay any sort of property tax, no matter how cleverly designed. But still, there were those of us who argued all year long for a smart tax with a smart design. One that got lots of information into the system, to enable the auditing that means everyone is paying the fair amount. And perhaps more importantly one that kickstarted economic activity, rather than just another form of income reduction.

Really, the whole thing was quite messy. One of your own agencies, the Land Registry – who can tell you who owns what plot of land and what’s on the land – was apparently not consulted once. The debacle of the Household Charge shows the same happened GeoDirectory, which is a database of addresses and their physical locations, maintained by An Post and Ordnance Survey Ireland, two more of your agencies.

The mess continued on Budget Day, when people were told they had to self-assess the value of their homes – but were given no good incentive to do so well. Some of us advised giving people a tax credit in Year 1 to have their property professionally assessed and in their tax return give the Revenue Commissioners the kind of information needed for good auditing. Instead, the door was left wide open for a most unwelcome experiment in game theory, where neighbourhoods come together and coordinate their valuations at below-market rates, leaving Revenue Commissioners powerless to find any individual resident guilty of tax evasion. Which is why they have decided to value the properties themselves, apparently. But of course, not least thanks to a rather detail-sparse Property Price Register, they have none of the direct information needed to do this.

So, as you’re quite fond of saying yourself, we are where we are. Now what?

As it happens, I actually spend quite a bit of my time worrying about how best to value properties, segment the property market, etc. I’m actually just fresh from a renovation of some of those models. And the good news is that with the right information – in particular a property’s size and location – it’s quite easy to come up with reliable estimates of a property’s worth.

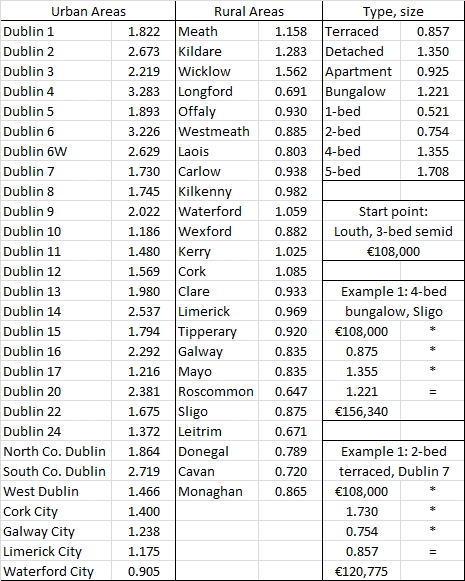

So, between breakfast and starting work this morning, I developed the following estimate of Irish property values. It should work in all areas, urban and rural, and for all major property types (apartments, bungalows, terraced, semi-d and detached) and sizes (one- to five-bedrooms).

So how does it work? To work out the value of a property, simply take the starting point (a 3-bed semi-d in Louth) and then multiply it by whatever factors you need. In particular, pick your county or urban area, if different; and pick your property type and size. So for a four-bed bungalow in Sligo, the €108,000 starting point is multiplied by 0.875 (prices in Sligo relative to Louth), by 1.355 (prices for 4-beds compared to 3-beds) and 1.221 (prices for bungalows, compared to semi-ds). Multiplying them all together gives an estimate of the property’s value in Q4 2012: roughly €156,000.

Hopefully, Mr. Government, this table is of some use as you try and disentangle yourself from yet another fine mess!

—

Some notes on the above table:

- Clearly, this is by no means meant to capture every last factor affecting property values. (One simple extension is number of bathrooms – roughly speaking, every additional bathroom is associated with a 10% higher price.) This model captures just under two-thirds of variation in house prices in Ireland, which – given the small number of factors included – is pretty good. But there’s still a third out there to explain. (Including effects for areas within counties would explain a significant chunk of the remaining variation, as it happens.) On average this will be right, and it will for the vast majority of cases be close but of course there are always properties that have unobserved factors that dwarf what matters for most homes. The method underpinning the figures above explicitly excludes outliers, so as to better improve the estimates for the vast majority of homes.

- The table above is based on 60,000 listings on Daft.ie over the year 2012, and allows for the fact that prices varied throughout the year. “Aha”, a sceptic might say, “these are only asking prices and sure we all know they are [insert pet peeve here – too high, too low, etc]”. As it happens, some pretty detailed research comparing asking and transaction prices shows they move together remarkably tightly, once controls for location and size are included (as they are here). Properties that sell typically sell for about 10% less than their asking price, so for that reason the starting point of €108,000 is actually 90% of the figure returned by the model. The key thing about the model is what it tells us about relativities (prices between counties), not necessarily levels.

- Lastly, lest there be any confusion, I offer this table as a public service but can’t offer it as any more than what it is – one academic economist’s analysis of the market.