This time last year, Minister for Finance Brian Lenihan announced, with the unveiling of NAMA, that all that was required for it to break even was for property prices to rise by 10% in 10 years. At the time, there were some – for example in the property industry – who thought this was “an easy ask”. And on the face of it, it sounds like an easy ask.

But there was a catch. It wasn’t that property prices would only have to rebound by 10% from wherever they bottom out. It was that property prices would have to be, by 2020, 10% above November 2009 prices. (November 2009 was subsequently set, for reasons best known to NAMA, as the final cut-off date, after which it would not be paying any attention to property prices.)

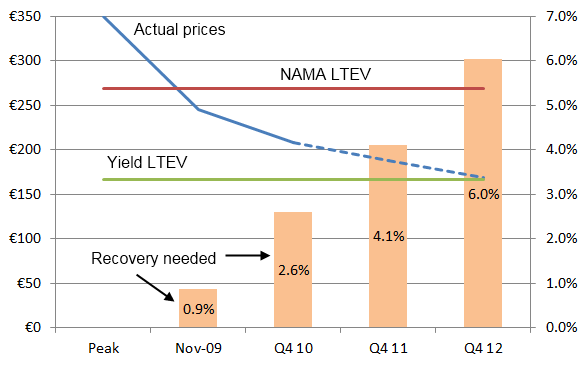

That is a very different proposition. It means that with each passing month of falling property prices since last November, it becomes more and more difficult for NAMA to achieve this “10% in 10 years”. Take residential property. Say asking prices peaked in early 2007 at an average of €350,000 across the country. By November 2009, the three main sources in the country – Dept of the Environment, PTSB and daft.ie – all showed an average fall of about 30% from the peak. This would mean that by NAMA’s cutoff date, it saw the average property as worth €245,000 and therefore that property’s long-term economic value as 10% above: €270,000.

What has happened since then? As we all know, property prices have continued to fall and, in all likelihood, will fall by about 15% between NAMA’s cutoff of last November and the final quarter of this year. This means that from a peak of €350,000, the average property value by late 2010 will be about €210,000. More important for NAMA than the comparison with the peak is the comparison with its break-even value: €210,000 is €60,000 below the break-even amount NAMA has set itself. So, instead of having 11 years to rise by 10%, we now have only 10 years to rise 30%. That’s an average annual rise required of 2.6%, and not the “easy ask” of 0.9%. Already, things are looking bad.

Unfortunately, simple mathematics means that this can get much worse. Suppose property prices fall by about 10% on average during 2011 (and there are surely few who would argue that the dynamics of supply, demand and interest rates will bring a significantly more optimistic outcome). The average home would be worth about €185,000 by then. We would now require a boom in property values of 45%, or 4% a year for nine years, for NAMA to break even.

Of course, all this is very easy with hindsight. How was NAMA to know that the long-term economic value was actually south of 2009 values and not north? Unfortunately for the taxpayer, any thorough analysis of residential property would have shown that this was the case. They wouldn’t have even needed to have paid any consultants. Any economist with access to the (free) Q3 2009 daft.ie rental report would have seen that the average yield for residential property across the country was 3.4%. NAMA itself set a target yield of 6%.

Suppose NAMA went a little bit easier on residential property and set an average yield of 5%, as not all purchasers of residential property, particularly in the family homes segment, are always watching the annual rental income. Then, it would have concluded that, if average prices were €245,000 in late 2009 when there was a 3.4% yield, then the long-term economic value of residential property was 32% below 2009 values, not 10% above. Again, this is not 20-20 hindsight, this is using the information available at the time. Many people, myself included and on more than one occasion, tried to make NAMA aware of this at the time.

The figures above are shown in the graph below. The blue line is what has actually happened prices. The red line is the NAMA long-term economic value, while the green line is long-term economic value according to the type of yield analysis which NAMA said it was using but doesn’t actually seem to have used. Figures for 2012 are also included, based on a scenario of a “final fall” that year of 10% (year-on-year), which would bring house prices back into line with a 5% yield.

I know that average property prices can be a bit abstract, so the light orange bars, which use the scale on the right-hand side, show the annual increase in property prices needed for NAMA to break even by 2020. One year on, 1% a year (the “10% in 10 years”) has already become 2.6% a year (or “30% in 10 years”). If house prices reach their true long-term economic value, NAMA may need a recovery of 6% a year to 2020 (or “60% in 8 years”) to break even. I wouldn’t want to bet on that.

—

PS. It should be pointed out that NAMA has not had things its own way on the calculation of long-term economic value. The European Commission has ruled, sensibly, that a euro in 2020 is not worth the same as a euro now. Through this stance on discounting, and through forcing NAMA to price better the effort spent taking over the bank loans, it has effectively wiped out the money that NAMA would have paid for its supposed long-term economic value upswing. That doesn’t, unfortunately, protect us from the downswing, though.

Baz ,

If we assume house prices get sensible and start to bear some resemblance to wages then a 2.6% per year rise is possible – as long as everyone starts to get inflation + 3% pay rises every year!

See, nothing to worry about.

Jagdip Singh ,

Hi Ronan

That’s an interesting article using your indepth knowledge of the Irish residential market, and I think you are right to highlight the risk to NAMA from future price falls.

However, 67% of NAMA’s loans are in Ireland, 27% in the UK and 6% in the Rest of World. Whilst Ireland is down 10% from last November 2009 (both resi and commercial) the UK is up 10% for commercial (3% for resi). The Rest of World is of course variable though the US and Canada appear to be off their knees. Also it appears that the majority of NAMA loans are commercial at heart with a minority (I’d estimate around 20%) being resi.

NAMA is paying for loans with 95% NAMA bonds and 5% subordinated debt (which is not honoured if NAMA makes a loss). So the €270k that NAMA paid in your example is in fact €257k if NAMA makes a loss.

Based on what NAMA has said about the geography of its loans and the breakdown between commercial and resi in tranches 1 & 2 and the fact that 5% of NAMA consideration is dependent on NAMA making a profit overall, I calculate that NAMA need see a 8.3% increase in current values today to break even at a gross level.

Of course if prices decline from today, then that increase required also grows. And of course NAMA needs to ensure that its operating costs and interest payable are covered with interest receivable and the cost contribution made by the banks (enforcement and due diligence) and the NAMA discount.

Ronan Lyons ,

Hi Jagdip,

You beat me to it – I was going to post that this is an analysis of residential property in Ireland, with obvious implications for land values, which to be fair are already far worse, and with close parallels in commercial property, although the rental adjustment may take longer to feed through in that market. It does not apply to the non-Irish segment.

My point is about method, rather than specifics. Naturally, non-Irish properties will be different, although not always a good news story. On the specifics, I would take the initial business plan, rather than tranches 1 and 2, for the commercial residential breakdown (although you’ll only get it for Anglo), as this is likely to be slightly more representative than the first two tranches, which were skewed towards (performing) investment properties and to the UK.

Thanks as always for the comment,

Ronan.

Joseph ,

On the subject of a chunk of their properties being in the UK, er, didn’t I see that Roubini was saying 2 consecutive months of (Nationwide?) index falls and property prices stagnating in the UK over the summer points to a fall coming their way soon?

Jagdip Singh ,

Joseph,

The general concensus is that resi in the UK will ease – its up 2.3% according to the Nationwide since last Nov (NAMA’s valuation date) but recent months have seen falls/small increases. There are outlying forecasts like a 25% decline in 2 years by Capital and the UK is in for some savage cuts to the budget – October should give greater clarity on that. However it is my belief based on what I know of the banks’ most recent accounts and NAMA statements (the geographical split above is from the draft NAMA Business Plan but was repeated by NAMA Chairman Frank Daly in Galway last week) that NAMA only needs a 8.3% [that’s very specific but I think a 10% increase is a fair assessment] increase from current levels to break even. If prices fall further or NAMA fails to break even on its operating costs/interest then that too is a cause for concern.

In fact I hear on the grapevine that NAMA may announce some highly profitable sales in the coming days (ie sold property for far more than was paid for it).

Ronan Lyons ,

Hi Jagdip,

Is your 8.3% assessment based on NAMA taking on residential property at 47% below peak (as the overall average figure announced in September last year might suggest), or on what NAMA’s legislation states it will value them on, current market value no later than November 2009? Thinking in rough terms (one quarter each for Irish commercial, Irish residential, Irish land and non-Irish), it’s hard to see how the 10%-in-10 years could be sustained if residential property in Ireland has fallen 15% and both residential and commercial property look like falling a further 10%+ over the next 24 months.

Paradoxical as it seems, much much more worrying is your grapevine news that NAMA will announce profitable sales. Firstly, it has control of a very limited supply of performing assets and should sell these sparingly. Due to political cycle concerns, however, it will be under extreme pressure to sell predominantly this type of asset before the next election, leaving us with rubbish that we can’t shift after that. Secondly, there is the whole McKillen court case – if that goes the wrong way, NAMA will have an appetite from “profitable sales” and start gobbling up performing investment portfolios as well as development loans. It sounds like an abstract worry, but it essentially means a lockdown on the investment property market, with knock-on effects for jobs as I discussed in the NAMA 2.0 post.

R

Paul Mara ,

Hi Ronan,

Thanks very much for such a thought provoking blog entry. I wonder what losses the country would see if the present trends in your estimates were to continue.

Given population and employment level changes as well, I also wonder how much these losses would be on a per resident and per tax payer basis in 2020.

It can’t hurt to have the information for potential outcomes, can it?

Paul

Jagdip Singh ,

Hi Ronan,

The 8.3% is based on NAMA taking on property at 30th November 2009 values plus a 10% uplift to long term economic value minus 5% overall if the subordinated debt isn’t honoured.

At 30th June, 2010 the PTSB/ESRI national price was 8.0% below PTSB national price at 30th November, 2009. So Ireland resi has dropped and indeed we may find at the end of Oct that Q3 PTSB has dropped again. PTSB is the only hedonic price series in the state based on actual selling prices, albeit from mortgage-only sales from a provider of less than 20% of mortgages in the State and based on an decreasing number of new mortgages.DAFT.ie provide an excellent guide from a large database but the basic problem is that prices are asking not selling.

But overall based on the geographical dispersion of NAMA assets (as contained in the NAMA draft business plan and repeated as still accurate by NAMA Chairman Frank Daly last week) and based on the analysis of NAMA-assets from the first two tranches (an analysis not refuted, though not proven either, by the latest banks’ financial statements) NAMA needs an 8.3% increase from today to break even.

There is a precise analysis of the 8.3% available on namawinelake, but the important point I would make is that NAMA needs a relatively modest increase from today to break even at a gross level. If prices continue to decline then that’s another matter. Also NAMA should be changing its valuation date to a more current date as that would save about €2bn on the purchase price of the remaining tranches as Ireland still accounts for 2/3rd of purchases and prices are c10% down on last Nov.

As regards what I understand to be soon-to-be-announced sales, the UK commercial sector is running out of steam – prices in August were up just 0.1% from July 2010. So sales now of some UK property which achieve 100% payback of loans (plus possibly some offsetting from borrowers’ Irish loans) may be terrific news for the taxpayer – it comes down to the price achieved and your view on the outlook of different property markets.

Ronan Lyons ,

Hi Jagdip, hopefully I’ll get a chance to review the namawinelake entry, sounds interesting.

One point that might help in future analysis is the very high (>95%) correlation between the three house price series (D/Envt, PTSB, daft.ie) since 2006. Asking prices may only be asking prices but their trend – if not their level – seems to correlate very well with closing prices. I understand that the D/Envt series is to be overhauled in the near future too, hopefully along hedonic lines.

R

Jagdip Singh ,

Hi Ronan,

I didn’t mean to dismiss the DAFT.ie reports on prices at all and as you say there is correlation between the differing report sources. I estimate that PTSB analyses 900 mortgages when producing its most recent quarterly price series. DAFT.ie has what 60,000 properties and of course crucially includes non-mortgage sales. The only detractor (and it’s a major one in my book) is that it’s asking prices which in a buoyant market may be exceeded and in the present market will probably be undercut.

Hopefully the House Price Database which MoJ Ahern has promised will be passed into law before Christmas will help generally (buyers, sellers, the property industry and the public, DAFT.ie, commentators) because at last we’ll have real numbers to report and debate.

Lastly for me on this, PTSB is down 36% from peak for Q2, 2010. Most commentators are predicting 45-50% drops (and there are outliers at 80%) so the core issue you address above, the possibility of future price falls, must indeed be of concern to NAMA.

mortgage overpaymen tcalculator ,

Hello there Jagdip, I really hope I’ll find an opportunity to evaluate the nama winelake post, looks fascinating. One point that may assist in long term evaluation is the very high relationship among the 3 home price set (D/Envt, PTSB, daft.ie) since 2006/2007. Requesting rates may only be requesting price ranges however their tendency – if not their degree – appears to correlate very well with final rates.