The 2010 in Review Daft.ie House Price Report is out this morning. Unsurprisingly, given the state of the economy and the mood of the nation in the final three months of the year, asking prices fell and fell by more than any other quarter of 2010. Nonetheless, the overall fall of the average asking price during 2010 of €35,000 is a good bit smaller than the fall of €60,000 seen during 2009 and indeed is smaller than the €45,000 fall seen during 2008.

Many people may engage in the sport of bottom-spotting by looking at how the speed of falls nationally is changing. However, to me, it is much more important to acknowledge that we don’t have a national property market anymore, what we have instead is a number of regional markets. My commentary on the latest Daft.ie Report, which follows, explains this idea in more detail:

The headlines from a review of the residential property market in Ireland in 2010 make unsurprising reading. 2010 marks the fourth year in a row where asking prices fell. Asking prices were 15% lower on average in 2010 than in 2009 and are now 40% below peak levels. One could make the argument that compared with a fall of almost 20% in 2009 the market looks closer to stabilising now than a year ago. But economic headwinds remain strong, with unemployment high, confidence low and those with static take-home incomes viewed as the lucky ones.

So what do we know at the end of 2010 that we didn’t know at its start, apart from the exact size of the falls in property prices during the year? I would argue that we know one very valuable thing: the underlying conditions in the property market vary so dramatically around the country that we should no longer be talking of a single national property market. Instead we should look at different regions as very distinct markets. This is important because it means that talk about “the property market” is essentially useless.

Back to supply and demand

To understand differences across regions, it’s worth recapping what we should be looking for in a healthy property market. Essentially, for a property market to find its new price level, there needs to be balance in the supply side of the market, i.e. no particular pressure on sellers to lower their price, and balance in the demand side of the market, i.e. no particular incentive for people to rent rather than buy.

The supply side will be in balance when there is no longer any overhang of properties for sale. Overhang refers to properties actively being sold, which we can trace using the total number of ads on daft.ie at any one time. Country-wide, there are almost 60,000 properties for sale on daft.ie, a figure that has not change significantly since mid-2008. It is important to remember that in addition to these, there are vacant properties currently not on the market that could be sold, in particular those in ghost estates.

What about demand? This brings up a whole host of factors, from changes in income tax to patterns of migration. But the simplest way of looking at whether the demand for buying properties is in long-term balance is the relationship between rents and house prices, known as the yield. For property, the yield should look like an attractive interest rate for savings, something like 6%. In Ireland, at the peak of the market, it had fallen as low as 3% and currently stands at just short of 4%.

Who’s closest to the finish line, in the property market adjustment race?

Therefore, when we look at conditions around the country, we should be looking at three things: the fall in prices from the peak, the total stock sitting on the market, and the yield on property. Using these headings, it is clear that the idea of a national property market needs to be retired. Certainly for the next few years, Ireland will be a collection of different property markets in the same country. At one end, there is Dublin, at the other end are the non-city parts of Connacht, Ulster and Munster, and in between are the other main cities and Leinster.

In what way are these property markets different? Ultimately, it comes down to how far along the path of adjustment they are. Take Dublin city centre, for example. Firstly, asking prices there are already 50% below peak levels. Secondly, the stock for sale sitting on the market in Dublin has fallen by 20% from the peak. Even allowing for properties for sale not listed on daft.ie, only about 2% of properties in the capital are for sale. The ghost estate problem is also smallest in the cities: Department of the Environment figures suggest that a further 2% of Dublin properties, mostly apartments, are in ghost estates. Lastly, the yield on property in Dublin city centre has risen from a low of 3.5% in 2006 to over 5.5% in late 2010.

At the other end, counties such as Mayo or Limerick have seen asking prices fall by just 30% from the peak on average. Across the non-city areas of Munster, Connacht and Ulster, there are over 37,000 properties for sale, which is not significantly lower than mid-2009, when the market was at its most crowded. These figures mean that almost 7% of properties in these areas are for sale. To this must be added properties in ghost estates, which constitute in many places a further 5% of semi-detached, terraced and apartment homes. Lastly, on the demand side, the yield on properties in these areas is still below 4%.

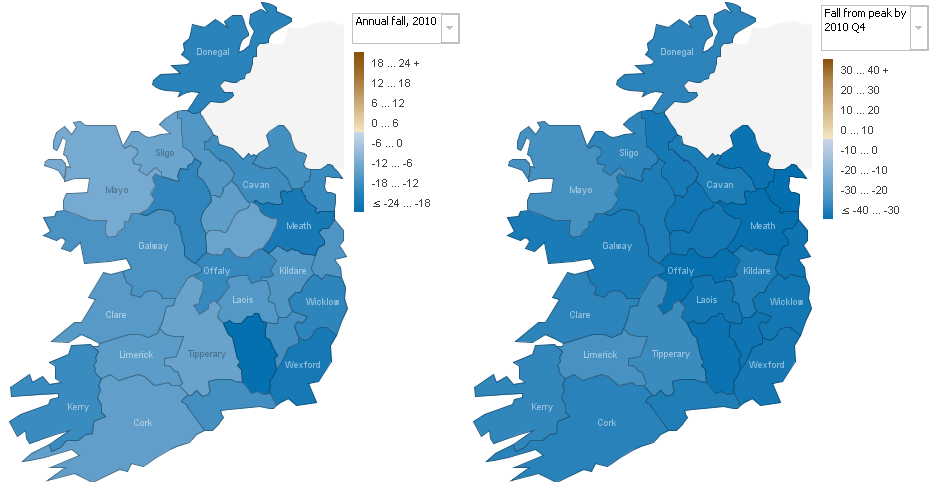

Over on Manyeyes, my favourite visualisation tool, you can have a look at the different county-by-county falls, across three headings – (1) in the final three months of 2010, (2) over the entire year of 2010, and (3) from each county’s peak (typically in early 2007). The annual fall and the fall from the peak is shown below. The pattern on the right-hand panel is relatively clear: the further east, the bigger the fall on average. But there is no similar pattern on the left-hand panel: the falls in Donegal, Meath and Kilkenny/Wexford stick out.

Where is the finishing line?

Naturally, no-one knows in advance the exact yield, and therefore the exact fall in house prices, that will bring Ireland’s property market back into balance. However, we do know that we are not there yet, as the market overhang persists and the relationship between rents and house prices remains out of balance. We can also say that whatever the ultimate yield and fall in prices needed, Dublin looks best placed to balance earliest, while those places away from the main cities and from Dublin’s orbit have taken the smallest steps so far towards sustainable prices.

Suppose the yield that will bring the property market back into balance is indeed 6% and therefore that the fall in prices from the peak is between 55% and 60%. If that is the case, while parts of Dublin may be close to completing their adjustment, some parts of the country are perhaps no more than half way through their adjustment process. This important distinction will be hidden if we continue to talk about a national property market.

Can anything be done to speed up the adjustment needed and prevent much of the country’s property market languishing for years yet? In theory, it’s as simple as sellers in rural parts of the country mimicking the discounts from the peak offered by their urban counterparts, and thus speeding up the adjustment process. But this is difficult as currently only larger population centres have the volume of transactions needed for sellers to judge market conditions. Ultimately, it comes down to information. Real-time publicly available information on transactions and prices achieved would be a significant aid for sellers all over the country and would help speed up adjustment in the property market back to sustainable levels of transactions and prices.

Eleven reasons to be cheerful | Ronan Lyons ,

[…] Browse All Posts « 2010 marks the end of a single national property market […]

Kevin O'Brien ,

At a meeting of the Urban Land Institute – John O’Connor (CEO of Housing and Sustainable Communities Agency) said that the current stock must be cleared.

Is there any data on how many houses are being sold?

Ronan Lyons ,

Hi Kevin,

Thanks for the comment. The best source in terms of timeliness is the IBF:

http://www.ibf.ie/gns/publications/research/researchmortgagemarket.aspx

However, they only give a breakdown by buyer type (FTB for example), and not by property type (new development for example). So it’s tough to know how much of the backlog is being whittled down each quarter, as opposed to houses merely changing hands or second-hand homes stay occupied following death or emigration.

R