Yesterday saw the annual awarding of the Nobel Prize in Economics. The economists awarded this year were Thomas Sargent and Christopher Sims. Much of their work is about understanding cause and effect in macroeconomic policy and the crucial role that expectations play. While some might argue about whether Sargent and Sims have taken economics down the right path, few could argue – looking at the world economy around them – that expectations and shocks are a hugely important topic.

Shocks and Great Expectations

The IMF produces twice-yearly estimates of their World Economic Outlook, complete with a dataset tailored for number-crunchers like myself. The dataset covers dozens of economic indicators for almost 200 economies, stretching back to 1980 where it can and also – crucially – giving forecasts for the coming five years. These forecasts are an excellent benchmark of expectations about future economic performance. Revisions to the forecast for, say, growth in 2012 across WEO reports tells us a lot about how economic conditions have changed.

We can see this by, for example, comparing the October 2008 and October 2010 WEO reports. The former would have been written largely before the tumultuous events of September 2008 and forecast growth in developed economies of 2.1% in 2009. For 2012, it predicted growth of 4.8%. The latter report showed growth in 2009 to be negative, at -2.4%, and its forecast for growth in 2012 was 4.1%. The first difference shows the impact of shocks – the second difference shows how expectations can change.

What has all this got to do with the Eurozone and sovereign debt crises? Well, according to the September 2011 WEO, the IMF estimates that this year the world’s developed economies will have a combined GDP of $40 trillion (that’s $40,000 billion). About $11 trillion of that is the Eurozone economy, a further $15 trillion is the US economy, with Japan, Korea, the UK and various other developed economies comprising the remaining $14 trillion.

This $40 trillion figure is about 6% below what the IMF expected it to be as of late 2008. Most would argue that the IMF’s expectations in 2008 – which reflect expectations of the broader economic community, including governments and the markets – were overly optimistic. The correction in expectations about what developed economies would look like in 2011 had already occurred by this time last year. Estimates from both last year and this year for 2011 GDP are close enough as to make no difference.

The cost of the debt crisis

However, looking to the future, one can see the cost of inaction around Europe’s sovereign debt crisis. The 2010 WEO estimated OECD growth over the period 2012-2015 to average 4.1%. The current estimate is for average growth of just 3.3%. In the Eurozone, the downward revision to growth has been even more dramatic. The average growth rate of 3.4% has been revised down to just 2.4%, a far cry from 2008 when the expectations were for growth of 4.4%.

The total cost to developed economies of the crises of the last twelve months amounts to lost growth of $1.3 trillion, or more accurately $1,342,000,000,000. Let’s face it – that looks like little more than an international phone number, making it very easy to forget that there are real jobs and incomes on the line – both ones that exist now and ones that do not exist yet but would have been created in the near future under different economic conditions.

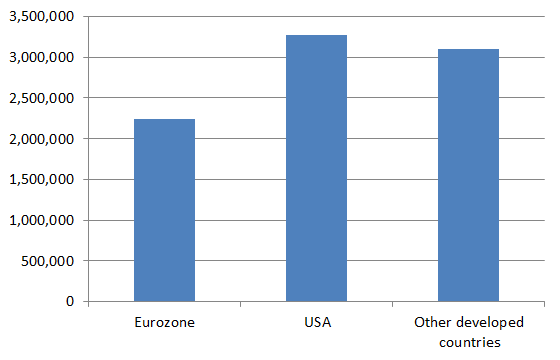

The graph below tries to correct for that. It takes the average lost GDP over the period 2011-2015 and expresses it as a multiple of GDP per capita for the Eurozone, the USA and the rest of the developed world. In other words, the graph shows the IMF’s implicit estimate of the number of livelihoods destroyed by politicians’ inaction regarding the sovereign debt crisis… over the past year alone.

There will be those who would argue that some of the livelihoods that will be lost were jobs that shouldn’t have existed in the first place – that what’s happening now is not so much the cost of inaction by political leaders by the inevitable consequence of the bursting of a global asset bubble. Even if they are right, it doesn’t really matter because it doesn’t mean that the losers are any less real. Anyone in Ireland will tell you, seeing large chunks of the population suffering from some combination of unemployment, negative equity and mortgage arrears, that it matters not one iota for public policy if one person’s lost job in construction was unsustainable while another’s wasn’t.

Talking to Peter Mathews, a banking expert and now TD (representative of the Irish Parliament) and government backbencher, he estimated that what is required is about a €75bn write-down of Irish banking debt, a similar amount for Portugal and slightly more for Greece. In other words, for the sake of about $300 billion in debt, which the markets believe are largely unsustainable anyway (hence the crisis), Eurozone leaders are willing to forsake $300 billion over the coming five years in output, jobs and livelihoods.

John ,

Hi Ronan, interesting post as always. I’m no expert on any of this, but as you say, some people would say some of those jobs shouldn’t have existed anyway. I’m just curious — what if that debt was written down? Wouldn’t that remove the economic and thus political imperative to push through austerity measures that would help bring us back to a base from which we can build more sustainable growth? I can imagine a danger of ending up in a similar situation with high debt again very soon if this debt is written down. I realise that the banking debt is not from the same source as more “normal” national debt, but if it’s doing any good at all it is giving politicians the ability to cut back on areas that traditionally would have been untouchable and maybe help reverse some of (IMO) the mistakes of FF.

It’s just a thought, and I’m not at all sure of how much sense this makes or particularly how fair it is (if that can even be established anymore…), and obviously genuinely sympathise with those affected by the cuts (as I have been and as have those of my immediate family!). Nevertheless, I’d be curious to hear your opinion on it since I’m no economist.

On a side note, as a number-cruncher yourself have you ever read Nathan Yau’s blog (http://flowingdata.com/)? If not, he’s got a great book out on visualising data that you might find interesting.

DowtheBow ,

Hi John,

Austerity measures will be pushed through anyway as th EU is trying to get every country to have a 3% Deficit. These were the original Eurozone rules but were largely ignored, but it is not sustainable to continue borrowing 50m a day to run the country.

It would mean however that the burden of debt would decrease so less of the tax take would be spent on servicing the debt and repaying bondholders every year