Research Interests – an overview

My two main areas of research are economic history and economic geography. In other words, both time and location matter when we want to understand economic outcomes, such as why certain cities or countries have higher living standards or faster growth than others. My D.Phil. at Balliol College, Oxford, which was awarded in July 2014, was on the economics of Ireland’s property market bubble and crash. Much of my research focus follows on from this and therefore currently I am working mainly on housing markets.

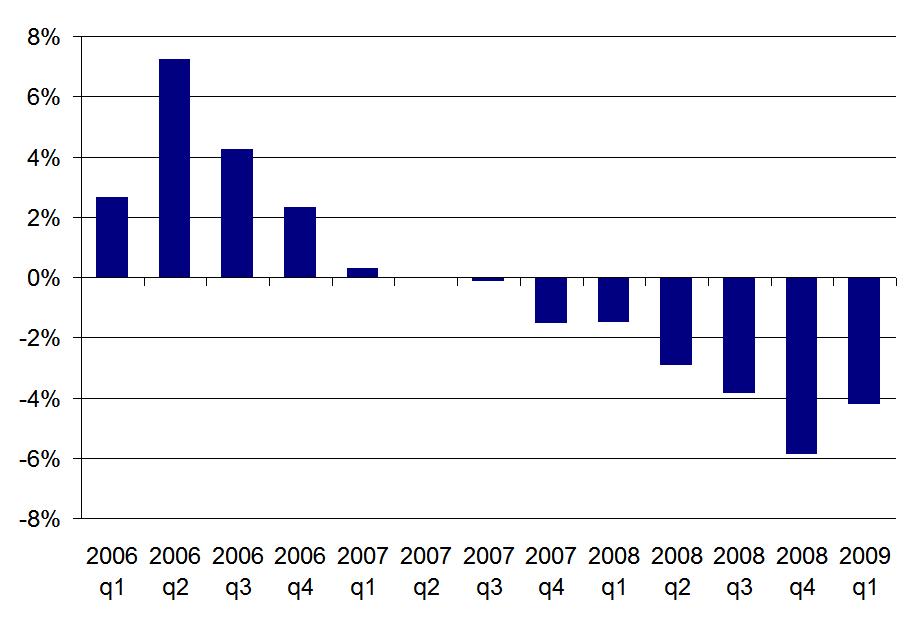

One strand of my research attempts to understand the impact of various factors – in particular conditions in the credit market and in the planning system – on the housing market, both in terms of house prices and units built. This involves developing measures of both credit conditions and planning conditions in the Irish context, as well as understanding the many interrelationships between house prices and other factors.

With the help of the team at daft.ie, I am also involved in measuring household expectations in relation to the housing market. What we think will happen house prices over the coming number of years has a huge influence on whether or not we want to buy. But what do we think will happen? And what shapes those expectations? I hope to find out.

Another strand of research I am actively working on is extending our frame of reference for the Irish housing market back, beyond the current ‘start date’ of 1980 or thereabouts all the way back to the mid-1800s. The first wave of globalization – roughly speaking from the mid-1800s to 1914 – was full of features we think unique to our age, such as sophisticated international capital markets, rapid technological progress and political backlashes to international trade. Thus, extending our frame of reference back can teach us a lot about what makes the current system different and whether it is stable or not.

This ties in with other cliometric (i.e. quantitative economic history) research I’m involved with. Together with Richard Grossman and Kevin O’Rourke, I have constructed a monthly share price index for Irish equities, going back to 1825. This lays the foundations for a range of studies, comparing trends in Irish wealth to similar trends elsewhere and to internal Irish conditions.

A final strand of research that I’ll mention here is amenity valuation. It is often said that markets have little to do with public services, such as schools, prisons and landfill sites, and almost nothing to contribute on what are termed ‘non-market services’, such as a walk in the park or summer sunshine. This is far from true, however. We pay for access to these amenities in part through the rent or mortgage we pay each month. I am analysing the relationship between house prices and a range of amenities, including proximity to schools, rail and road infrastructure, flood risk, and green space. A better understanding of the benefit these amenities give allows us to spend public moneys better.

A list of publications, working papers and projects is available here.