Lessons from Saskatoon: allow people to cluster

A decade ago, I worked with IBM, as an economic consultant as part of their team serving governments and public sector clients around the world. One of my more unusual trips involved a stop-off in the city of Saskatoon. For those who’ve never been, Saskatoon is one of the main cities in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan, which is smack bang in the middle of Canada. It’s a resource-rich part of the world, home to a lot of the planet’s potash and uranium.

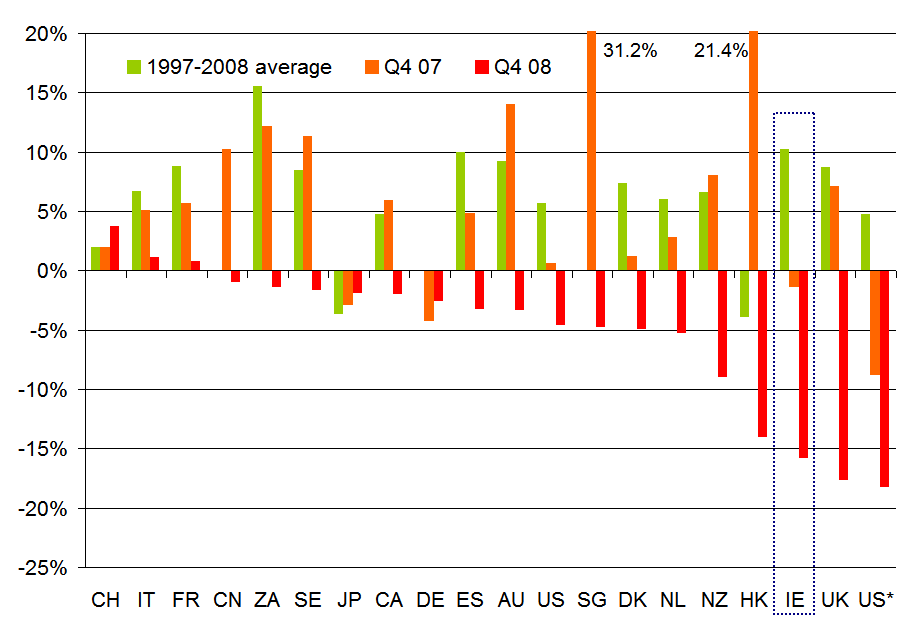

One of the reasons I was there was to talk about Ireland’s business model. It being 2007, they were curious about how a country like Ireland – with no natural resources to speak of – was as rich as it was. One of the things I took away, though, was just how powerful our tendency as humans to cluster is.

Canada is a huge and sparsely populated country. At roughly 2.5 billion acres, if the entire human race broke up into families of three, we’d each have an acre. And yet, here in the middle of the vastness of Canada, a classic ‘Central Business District’ rose up into the sky. With no scarcity of land, there was still a cluster of tall buildings in the middle of the city.

This was not some quirk or a vanity project of empty buildings. Instead, it reflected one of the counterintuitive aspects of human nature. If you free us up to move and work wherever, instead of finding our acre away from everyone else, we will instead look to live near others.

The current tally for Saskatoon, a city approximately the same size as Cork, is roughly 50 buildings at least ten storeys tall. Five of these are currently under construction. When it comes to accommodating its own growth, Saskatoon is not putting the brakes on.

Clearly, central to this is regulatory permission to build tall. There are perhaps half a dozen buildings in Ireland more than a dozen storeys tall. This does not reflect a lack of demand. In a city as big as Dublin, without restrictions on heights, there would probably be close to a hundred buildings ten or more storeys tall – and in all likelihood a few of those would have more than thirty storeys.

But Dublin – together with other Irish cities – have local authorities that tend to frown on height. In Dublin City Council, for example, height is proscribed in most of the places where there would be demand for it: the centre of the city. Instead, if you want to build tall, you are encouraged to look in more experimental locations – including Ringsend, North Wall and Ballymun.

Trying to shoehorn demand for height into parts of the city where demand is unproven is not a recipe for success. But this may sound like a victimless crime: city fathers want developers to build tall where there’s no demand – developers don’t build because the demand is not there. Who loses, right?

Unfortunately, these actions have opportunity costs. In fifty years time, Ireland is projected to have an extra 1.5 million residents. Not only that, Ireland will be an 80% urban country by then, the same as its peers, and the bulk of its households will contain just one or two persons.

Add all that up and the prognosis is clear: Ireland needs to densify, rather than sprawl, and central to that is the construction of a large volume of urban apartments, of all kinds, over the coming decade.

But building apartments is a very different activity to building housing estates. In particular, the risk profiles are worlds apart. When building a housing estate, you can build ten or twenty semi-detached homes, test the waters and then use the proceeds to fund the next 30 or 50 homes, if the demand is there.

When building apartments, just like building a hotel or an office block, it’s all or nothing. No apartment is finished and ready to be occupied until they all are. For that reason, policymakers here need to understand how apartments are built, from start to finish, and ensure their rules are future-proof.

In particular, it’s emerging elsewhere as something of a rule of thumb that when developing a build-to-rent apartment block, 500 units is the minimum efficient scale. This means height, not width. But if our main cities have rules that prevent the height needed, then can we really expect to get the homes we need?

It’s time for our local authorities to look around, learn from their peers and future-proof their development plans.

==

An edited version of this post was originally published in my column in the Sunday Independent.