The first house price index based on the house price register

Over the weekend, the Sunday Independent featured some analysis I’ve done with the help of the team at Daft.ie on the Residential Property Price Register (RPPR). The full report is available here (PDF) – in this post, I’ll give a quick overview of what we did and what we found.

What is it?

The aim of the exercise was to produce a property price index for the residential market in Ireland, one based on transactions price (as per CSO but not the existing Daft.ie asking price index) and for all properties, not just mortgage-backed ones (as per the existing Daft.ie index, but not the CSO).

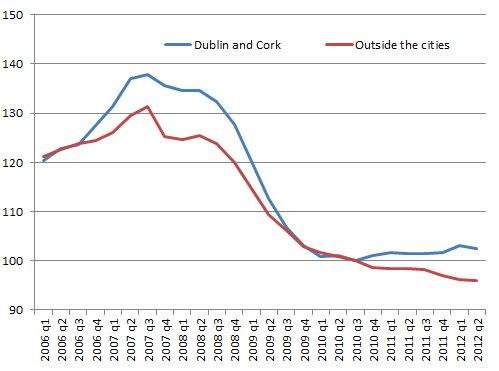

Many, such as NAMAWineLake, greeted the RPPR as the end to all existing property market reports but unfortunately, it’s not quite that simple. The Register certainly gives us valuable information on the number of transactions, by county and by month – and ultimately, it is volume, not value, where we will see a property market “recovery”.

The Register contains no information, however, on property type or size. Without this information, the only vaguely reliable statistic on trends in property prices is the median price. And even that is of limited use, in a market with an anaemic level of transactions, as I pointed out earlier in the month.

Luckily, where it is possible to connect up addresses in the RPPR with addresses in very large datasets of properties, such as the Daft.ie archives, then the attributes needed for a house price index – in particular location, type and size – can be added in and standard methods applied to develop a house price index for Ireland.

How was it done?

The first part of the exercise was matching up the transactions with properties in the Daft.ie archives. Fortunately – given I’ve no idea how to do this efficiently – I was not involved in this task, which was led by Paul, Head of Development at Daft. They managed to identify a property type (detached, semi-d, terraced, bungalow or apartment) for just under 20,000 transactions. Adding in information on bedrooms and bathrooms reduced the sample to about 13,500 transactions.

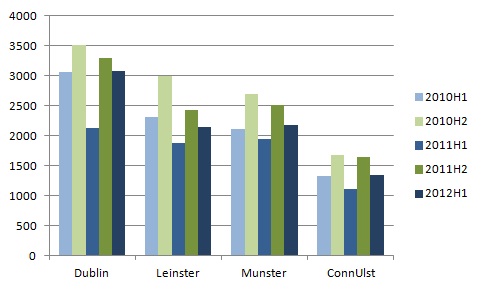

For these, we have all the information needed to conduct hedonic (i.e. like-for-like) analysis. How representative is this sample? The bad news is that we cannot know for certain – if we knew more about the properties excluded, we wouldn’t have to exclude them. The good news, however, is that for the main heading we do know (county), they look to be representative. The proportion of all transactions that made it in the sample for analysis varies only from 28% in Leinster (ex-Dublin) to 23% (in Connacht-Ulster), with the figure for urban areas and Munster being 25%.

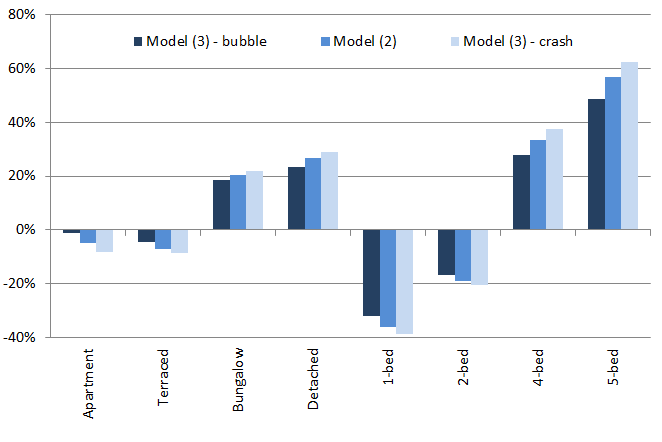

The model applied breaks down each property’s price into five components: time of transaction (by quarter), regional market (six within Dublin, the other cities are each one, and each county is another regional market), number of bedrooms, number of bathrooms (relative to bedrooms) and the property type.

The full model interacts the bedroom and type variables, as well as the quarterly trend, with broad region (Dublin, Other cities, Leinster, Munster, Connacht-Ulster). This is to allow property differentials to vary around the country and also to allow the trend to vary by region. For technophiles, the method is a pooled semi-log hedonic regression. The model explains over two-thirds of the variation in house prices (the R-squared is 68.4%).

One other methodological point is warranted. The dataset is a messy one, with outliers due to errors and to extreme or unusual properties. To combat this, a relatively standard two-step procedure is used. At the first stage, the model is run and then the model’s prediction is compared to the actual price. Where the actual price is more than twice or less than half the predicted price, clearly other factors are at work for this property. These are then excluded. It’s worth noting that the number of properties excluded by this method (roughly 7%) is below the similar proportion in the CSO index.

What did you find?

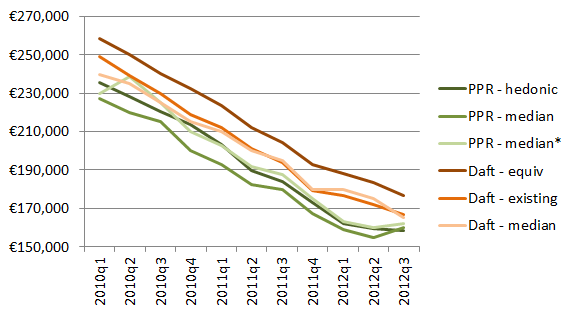

Now… on to the goodies. The first graph above shows the average property price for a number of methods. The national average is calculated with each ‘regional market’ having a weight equal to its Census 2011 share. Three datasets are used: the full RPPR (50,000 properties; median only), the subsample of the RPPR used here (13,500 properties; both median and the results from the hedonic exercise described above), and the Daft.ie listings 2010-2012 dataset (200,000 properties; the existing methodology (a variant of the above), the methodology described above applied to this dataset; and the median).

There are a couple of points worth noting. Firstly, while the two median series based on RPPR data point to a small increase in prices in Q3 2012, this increase disappears using the like-for-like method (as I suggested it might). Secondly, the average price in all three Daft.ie series is above that in all three RPPR series, and this is especially the case when the model described above is applied to Daft.ie listings. This suggests that in general asking prices are 10% above transaction prices. (This latter fact is probably due to the fact the full Daft.ie listings model can include a variety of sub-county controls, something the limited transactions in the RPPR cannot do.)

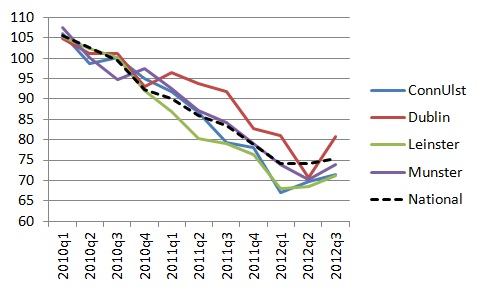

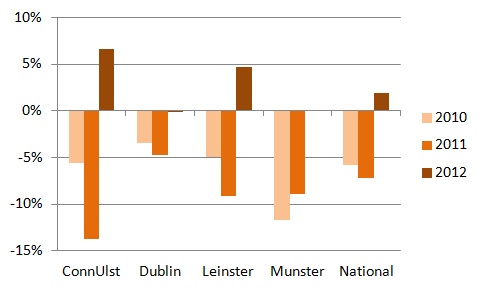

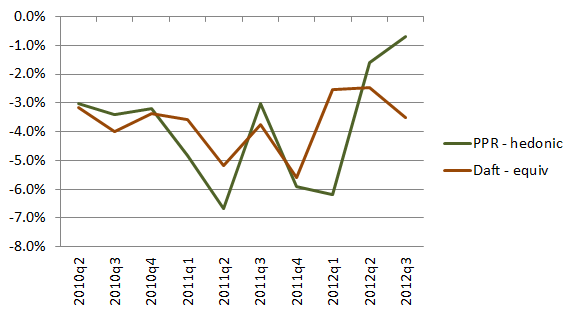

The second graph (above) shows the quarter-on-quarter change in RPPR transactions and in property listings. Again, I took two things from this graph. The first is that by and large, they tell the same story – when list prices fell more sharply, so too did transaction prices. The difference at the end is certainly not typical and perhaps more noteworthy for that.

Secondly, both series point to much tougher market conditions in 2011 than in either 2010 or 2012. The average quarterly fall in prices in 2011 was 5.1% (in the RPPR series, 4.5% in list prices), compared to 3% before/after. Put another way, prices in 2012 Q3 were just 2.3% lower than in Q1, whereas twelve months previously they had fallen 10% in the same period. (For reference, they fell by 6.3% during the same period in 2010.)

The Daft.ie RPPR index is shown in the table below, alongside the existing Daft.ie asking price index and the CSO index, each of which has been rebased so that the average for 2010 is set to 100. The correlation between the RPPR index and the CSO index is 99.8%, while the correlation with the Daft.ie asking price index is 99.7%.

So what?

Those whose time is tight might be wondering what’s new in all this. In one sense, there’s not an awful lot of “new news” in this. Prices are close to stable but are falling gently still… but not at anything like the speed we saw in 2011 – “but sure we knew that from the CSO and Daft.ie reports anyway”.

The value in adding an RPPR index (as the Daft.ie Report will hopefully be doing from now on) is not that it will reveal necessarily anything hugely different from other sources. Rather, it is another signal from the market and together all these signals will paint a picture. This will come as a disappointment both to those hoping prices had actually been rising secretly and to those hoping they’d been falling sharply still. But to the rest of us, the fact that all market signals are saying roughly the same thing is welcome news: it will make it all the easier to know when the property crash is over.