Brisk business at the top end of the housing market once more

The latest Daft.ie Wealth Report shows that – as prices continue to rise – so does Ireland’s housing wealth. There were over 800 transactions of at least €1m during 2017 and by all accounts there will be even more seven-figure purchases this year.

When a property is transacted, of course, that wealth is – at least for an instant – liquid cash. Most of those selling a property soon buy another so the wealth becomes embodied once more in real estate form.

Another equally important question, though, is who is sitting on a property worth a million. Daft.ie’s Wealth Report is the only one of its kind to estimate the number of property millionaires in the country. It does this by using a detailed form of analysis, looking at the value of 25 different property types in almost 400 micro-markets around the country.

Of these nearly 10,000 segments, just 58 have an average value of over one million euro – from four-bed terraced homes in Sandycove to five-bed detached homes in Ballsbridge. These property segments cover an estimated 4,600 dwellings.

This is an increase of almost 20% in the number of property millionaires in the space of just one year. A year ago, there were just 3,800 property millionaires. In other words, rising property prices over the last year have created more than two new property millionaires every day!

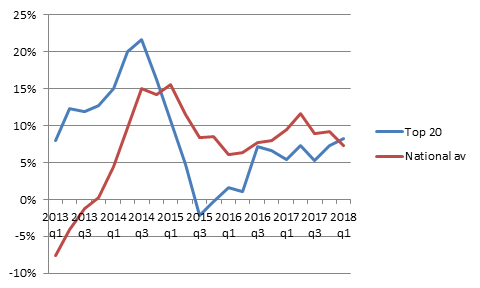

How is the top end of the market holding up? The figure accompanying this piece shows the average annual change in property prices across Ireland’s top 20 markets. All are in South Dublin, with the exception of Howth and Enniskerry.

The pattern is clear: before the Central Bank rules came in, these markets were taking off, with prices in late 2014, just before the rules were announced, running at more than 20%. The rules coming in saw prices stabilise, with almost no change between the third quarter of 2014 and the first quarter of 2016.

Since then, though the lack of supply and strong demand have caused inflation at the premium end of the market to tick up again. And in early 2018, for the first time since the Central Bank rules were introduced, inflation at the top end of the market was higher than the national average: 8% compared to 7% nationally.

At least some of this push at the top end of the market is Brexit-induced. Anecdotally, architects will tell you stories of couples returning from London with a seven-figure budget buoyed by the extraordinary level of prices in the British capital.

On top of that, it seems clear that any Brexit dividend in terms of FDI jobs will be at least as large in the tech sector as in financial services. The on-going uncertainty around the nature of Brexit has meant that the ‘born online’ firms – most of who have large operations in both Dublin and London – are favouring the Irish capital for new projects.

This stems from an uncertainty about whether their highly-skilled and very multinational workforce will be able to enter and stay in the UK, once it leaves the EU. Ireland has remained explicitly open for business – issues around housing and visas aside – and that certainty appears to be reaping rewards.

The premium end of the market is always going to be the most illiquid. If you have a €5m home in Temple Gardens or Eglinton Road, your pool of buyers is always going to be far smaller than if you have a €500,000 home in Rathfarnham or Raheny.

That lack of liquidity can trick some commentators into thinking the market at the top is in trouble. The figures here show that this is not the case – at least not currently. The market for Ireland’s most expensive homes is booming currently.

What underpins the top end of the market? Looking through the list of areas that make up Ireland’s Top 20 markets – Killiney, Dalkey, Sandymount, Sandycove, Enniskerry, Howth and Rathmichael, for example – it is clear that nature is a luxury.

Natural features such as mountains and coastline are over-represented at the top end of the housing market. The richer we get, it seems, the more we want to be able to enjoy what nature provides for free, either as a picture out our window or as a playground outside our front door.

Nature may provide these things for free – but they don’t come cheap in the housing market. New research I have been working on, jointly with Stephen Hynes and Tom Gillespie at NUI Galway, finds that natural amenities add significantly to property values. The best located properties – those with not only the views but on the coast too – are on average a third more expensive than similar dwellings, at least in structure, but without the same amenities.

If nature is one of the luxuries at the top end of the Irish housing market, history is the other. Many of the areas I mentioned above – together with others in the Top 20 such as Ranelagh, Rathgar and Ballsbridge – are home to some of Ireland’s finest older homes.

By definition, you can’t build Victorian or Georgian property now, so this limited supply gives those homes added attraction in the market. One of the contradictions of the housing market is that both energy efficiency and age are prized in the market. Joint research with Sarah Stanley and Sean Lyons, of the ESRI, found that “vintage premiums” are understated if you don’t take into account energy efficiency. Compared to similar properties built in the 1990s, properties built before World War 2 is worth 20% more – but if you left out energy efficiency from the model, you might think the premium was just 15%.

Scarcity, in other words, is what drives the top end of the market. And with lots of demand – and based on Brexit uncertainty, this seems set to continue – it seems the coming year will create even more property millionaires.