This is an unabridged version of my commentary on the latest daft.ie report (2008 in review), which is available at daft.ie/report.

When we look back at 2008 in a few years time, I think it’s fair to say we will regard it as the annus horribilis for Ireland’s property market. In late 2006, we issued a report which was the first to spot a slowdown in the property market. At the time, it was our view – unpopular though it was – that rising interest rates and high levels of supply would lead to a levelling off in house prices. This turns out to only have been the start of the story.

Ireland has become a bit of Britney Spears economy. Bursting onto the world stage at the end of the 1990s, Ireland was heralded as an economic phenomenon and rapidly became a global superstar and poster-child for economic development. But recently it looks like it’s all just falling apart. Nowhere is this more evident than in Ireland’s housing market – until recently the engine of Ireland’s economic growth. House prices have fallen significantly from their 2007 peak, with trends in Ireland’s property market driven by the ongoing effects of overproduction of housing, combined with extraordinary international economic developments.

As the daft.ie review of Ireland’s property market in 2008 shows, asking prices for Irish property fell on average 15% during the last year. That makes 2008, in many ways, the opposite of 2006. While asking prices were static throughout 2007, the 12 months of 2008 have seen the typical home lose just over €50,000 in value, almost the exact amount gained in 2006. Ireland’s average asking price of €295,000 in December 2008 is almost exactly the same as that in January 2006. Even the property market’s quarterly trends were like 2006 in reverse.

The early part of the year was marked by uncertainty about growth in developed economies, as ongoing financial turmoil took its toll on share prices and the dollar. There was still a widespread belief, however, that emerging markets would take up the slack and that we were experiencing a blip rather than a derailment. Asking prices therefore eased back just 1.4% in the first three months of the year. As summer came along, though, it seemed that we were entering a new economic era, one of $200 oil and inflation. As this sank in, confidence took a further hit. Asking prices fell twice as fast between April and June as they had done in the first quarter, with the outer commuter counties of West Leinster, more dependent on petrol prices than elsewhere, particularly badly hit.

As autumn descended, the full extent of the financial crisis was revealed. Long-standing banks and investment houses were wiped out or nationalised on a weekly, if not daily, basis. House prices fell almost 4% in the three months between July and September as a result. There was still a feeling, however, that the financial and real economies, or Wall Street and Main Street as they were dubbed, worked in somewhat separate spheres. As the year came to a close, however, the full impact of the financial crisis on the real economy was becoming apparent, with job losses in retail, catering and manufacturing. The largest fall in asking prices, almost 6%, has come about in the final months of the year (just as the largest rise occurred in the first part of 2006).

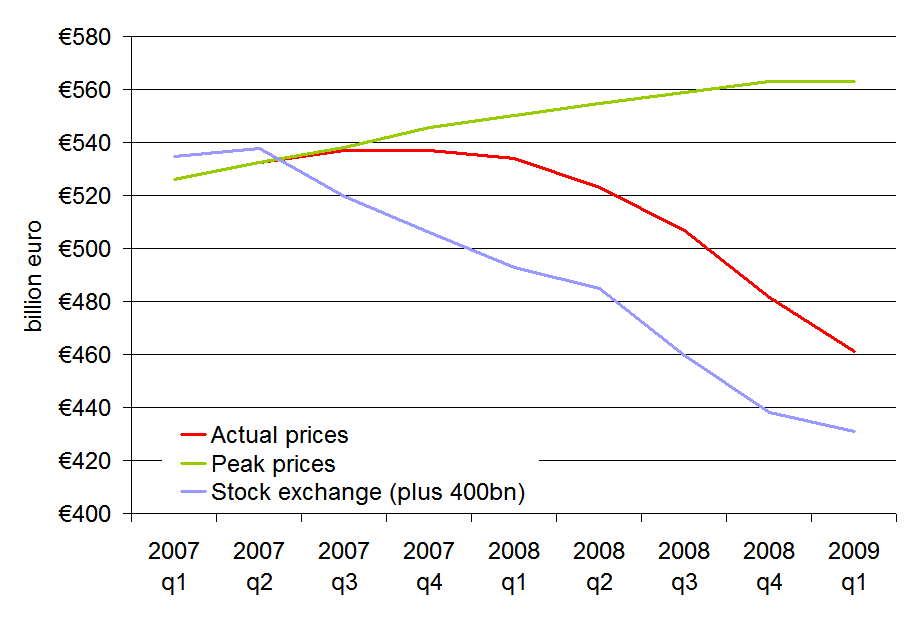

South County Dublin has been in many ways the flagship of Ireland’s property market. Average asking prices in the area rose from €530,000 in early 2006 to over €680,000 by mid-2007. They have fallen steadily since then and in late 2008 fell over €50,000 to stand very close to their early 2006 levels. Elsewhere around Dublin, the fall from the peak has been in the region of €70,000 to €80,000. Outside the capital, falls in asking prices of between €40,000 and €50,000 from peak values in mid-2007 are more typical.

A range of global economic developments has made it necessary for countries around the world to revise down their growth estimates over the coming years. Russia, which earlier in the year had been expecting growth in 2009 of perhaps 7%, is now fighting talk that it is already in recession. The US may experience its first two-year recession for some time, while the IMF believes that the world as a whole will be in recession next year, according to its definition of global growth of less than 3%.

Ireland was delicately poised atop recent global economic trends. Its two major currency exposures are to the dollar and to sterling, so recent depreciations of both are having a major impact for Ireland’s exporters.

In the midst of all these external developments, Ireland’s domestic sector – so heavily reliant on construction for employment, wages, tax revenues, and general sentiment – has contracted sharply. The government budget shortfall for the year totalled €8bn, with likely implications for public sector pay and employment in 2009 and 2010. It is likely that net migration will change from large inflows in 2007 to outflows in 2009, particularly as unemployment looks likely to reach double digits at some point in the next few months.

What do all of these local and global trends mean for homeowners and prospective first-time buyers? To see where the property market will go next – and when it is likely to recover – it is necessary to look to the past as well as to the future. Over the past few years, Ireland has built perhaps twice as many houses as it needed, due in large part to tax incentives. Between 2005 and 2007, a quarter of a million new homes were built in a country that only had 1.4 million households in 2005. Worse still, due to the nature of the tax incentives, many of these properties were built in areas that did not need them. It stands to reason that if you build twice as many houses as you need for three years, you’ll need to build half as many as you need for six years to get back to equilibrium.

So should we write off Ireland’s property market until 2015? Not necessarily. It’s likely that prospects will vary from region to region. As outlined above, areas like South County Dublin are certainly feeling the pinch now, falling almost €150,000 on average from peak values. In such areas, prices are determined less by wages and interest rates, and more by expected future value and confidence. Therefore, whenever sentiment eventually reverts to a more optimistic outlook, those areas are likely to rebound faster. With the government seemingly tied into a pro-cyclical trap and not able to implement an economic stimulus package, due to large increases in public expenditure in the good times, it is of course an entirely different question whether lower interest rates will be enough to kick-start sentiment in Ireland.

In other regions, the long-term prognosis is very different. For properties close to centres of employment, four elements – employment, wages, interest rates and access to finance – will be crucial. Other areas, suffering from a glut of properties, may need a longer or a larger adjustment. Ballpark figures, based on the 2006 Census and daft.ie listings, suggest that as much as 10% of properties are for sale in counties like Roscommon, Cavan and Leitrim, compared to less than 5% elsewhere. It won’t be impossible to sell properties in these counties in coming years, but sellers must be realistic about the value of their property in a flooded market.

As I mentioned at the start, Ireland has been in many senses the Britney Spears of the world economy over the past ten years. Bursting on to the scene in the late 1990s, we earned worldwide recognition for how much we achieved so fast from such humble beginnings. With all this fame, it was perhaps to be expected that we lost our way in the early years of this decade. Recently, things have got a lot worse. With bank bailouts, budget debacles, job losses and public sector cuts, we’ve been through it all. Nonetheless, like Britney, while a lot of damage has been done, with good management, we can look ahead and spot elements of a brighter future – just look at the cost of petrol, mortgages, food or clothing now compared to a year ago. Ultimately, with the resolve to put right what needs to be fixed, and with a far better starting point than we had in the mid-1980s, we have to be confident about our prospects for the future.