Information a key ingredient to having a healthy property market

The imminent publication of the house price register, where from June this year all members of the public will be able to find out the transaction price of a particular property, can only be welcomed by those interested in restoring Ireland’s moribund property market to some sense of normality.

The recent economic history of Ireland’s property market is well known, not only in this country but the world over. From the 1990s until the mid-2000s, the world economy was one of many buoyant property markets. Since 2007, prices in many major markets, including large parts of Europe and the U.S., have fallen significantly. And in that story, Ireland sticks out, with the largest rise in house prices of any developed economy in the decade to 2007 – 300% if anyone needs reminding – and the largest fall in the five years since – over 50% as of late 2011.

Why Ireland sticks out

But why was Ireland’s bubble-crash cycle so vicious? While there is a long list of potential suspects, three factors that distinguish Ireland from most other countries must shoulder the lion’s share of the blame. One was opening the floodgates of Eurozone credit to an Irish banking system that had up to that point only ever been used to having to fight for every pound. A second factor was Ireland’s extraordinarily generous treatment of property as a form of wealth: Ireland was, as of 2005, the only modern economy where citizens neither paid an annual property tax nor capital gains if they sold their house at a profit. (Indeed, the situation is worse now, with the only substantial property market tax that existed in 2005, stamp duty, effectively abolished.)

The third factor – and perhaps the least excusable – was the poor quality of information available to those transacting in the property market. To see why this matters so much, we need to go back to how the property market works. The price paid for a property today reflects people’s expectations of what they think will happen property prices tomorrow, next year and over the coming generation. This makes our expectations of fundamental importance.

People’s expectations of house prices are what economists call adaptive: if they see prices having risen by 60% in the last five years, most assume that something similar will happen the next five years. And sure enough, if you look at the ESRI survey of consumer confidence from early 2007, most people thought that house prices would increase by as much between 2007 and 2012 as they had done between 2002 and 2007.

The importance of expectations

But of course we know that is not what happened. So part of ensuring that the bubble and crash we have just experienced never again happens involves not only fixing how banks themselves borrow – and how society taxes property – but also improving how people form their expectations of house prices. Think back to bubble-era Ireland. Then, we had a situation where the price of an off-plan apartment would be higher on a Monday than the previous Friday. Why? Because in the frenzy, nobody knew what anything was really selling for – and to avoid getting caught out, they effectively gazumped themselves.

The best tool to fight this type of situation is information and the house price register is the most obvious step forward. There will of course be those that think it is nothing but an annoying invasion of privacy. But they need to think of others. After all, buying a home is the largest transaction that most people will ever engage in – surely it is only reasonable that we give our young families as much information as possible before they take the plunge.

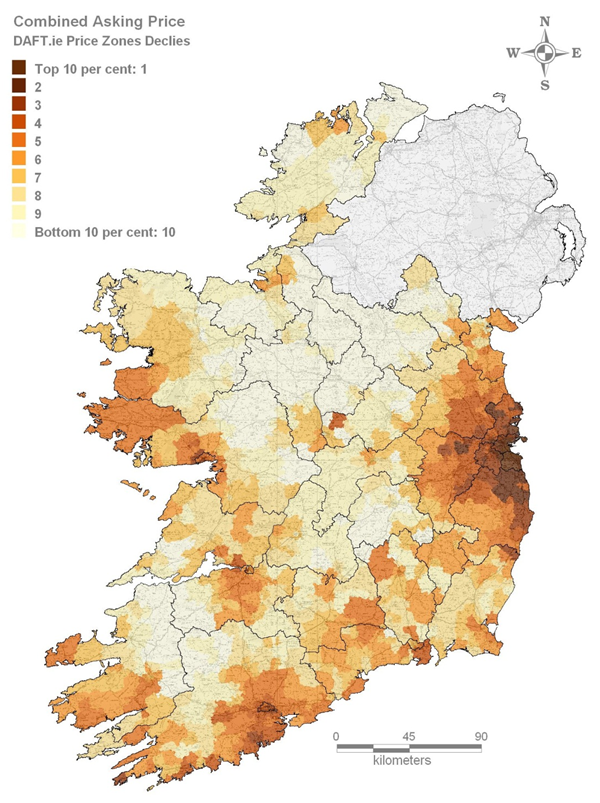

The house price register will do this. Members of the public will be able to go on to a map of Ireland, click on their area of interest and see all recent transactions, their addresses and their prices. In the early years, it seems other information – such as property type, building size or site size – won’t yet be available but given the huge amount of work being done in digitizing Land Registry records and local authority Development Plans, it’s only a matter of time before the “informational infrastructure” available to Irish people becomes even better.

Aside from perhaps the labour market, there is no more important market in any modern economy than housing. In Ireland, we (still) hold some €300bn in residential property alone. All types of real estate make up probably three quarters of our wealth, while housing makes up more of the country’s “basket of goods” than any other good or service. The links between housing and the broader economy have gone from being underappreciated by economists ten years ago to a hot topic of research now. In the Ireland of 2012, with widespread unemployment, negative equity and growing mortgage arrears, those links are all too real.

Make no mistake – the house price register will not be a panacea. But it is an important step in normalising Ireland’s property market and creating a healthier link between it and the rest of the economy.

—

This post originally appeared as an op-ed in the Irish Independent last week. It does not seem to be available online but its companion piece, by Michael Brennan, is available here.