“I could be a millionaire if I had the money. I could own a mansion, no I don’t think I’d like that…”

So sang Clifford T Ward in his beautiful song, “Home Thoughts from Abroad“. While wealth and property may not have had an allure for him, the two topics have dominated Ireland’s recent economic history, since a domestic property bubble fuelled by inappropriately low eurozone interest rates replaced competitiveness and net exports as Ireland’s primary growth driver about ten years ago.

Last Friday, while enduring the worst economic contraction of any developed economy since economists and statisticians started measuring these things, the Irish people went to the polls. They did so amid much international attention, as Ireland’s government was the first of the eurozone to be a casualty of the ongoing debt crisis. The result was utterly unsurprising to poll-watchers yet still momentous: the two parties of the outgoing government saw their representation reduced from 83 seats (77+6) to 20 (20+0!).

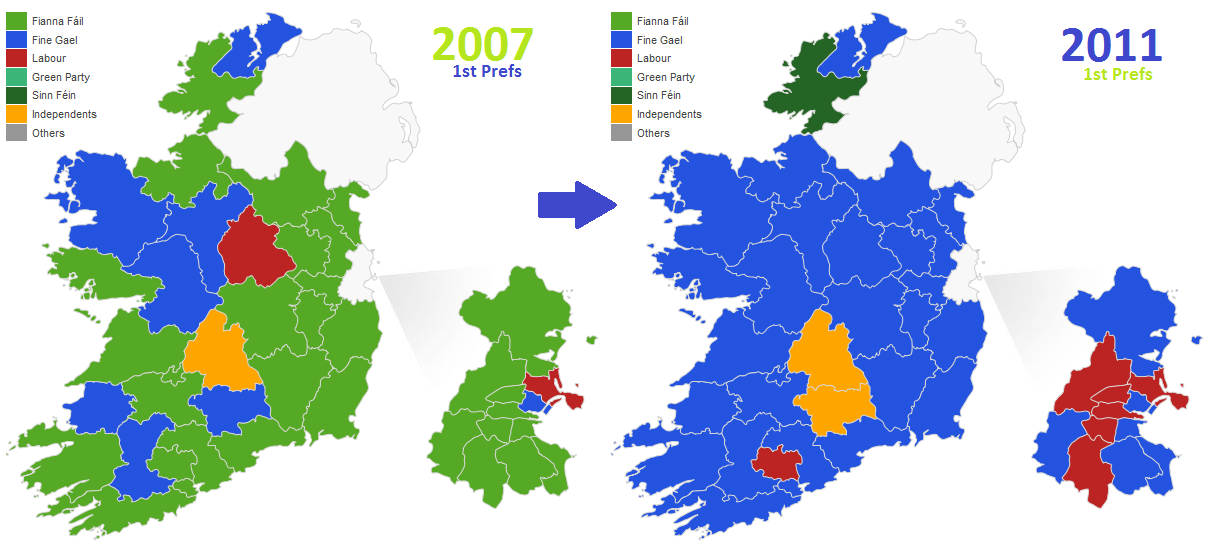

Even to an outside audience, this is a remarkable turn-around in fortunes. What makes it all the more momentous is that the largest party, Fianna Fáil, which had never before in its history received less than 39% of the first-preference vote, garnered just 17% of the vote! The graph below – which is courtesy of state broadcaster RTE – shows which party topped the poll in each constituency in 2007 and again in 2011. The complete disappearance of light-green is a picture worth a thousand words.

But for all the interesting theses generated for future PhD students in political science, do we know anything now that we didn’t know before the Irish election? I would argue that we know three things.

(1) Ireland voters have emphatically ruled out sovereign default…

Ireland and Greece are very different animals. Greece has walked itself, through bad fiscal management and even statistical deceit, into an unsustainable debt position. Faced with this prospect, many Greeks have taken to the streets, arguing among other things that the required realignment of taxation and spending is somehow a transfer from poor to rich. The situation in Greece looks increasingly unsustainable and it is perhaps only a matter of time before its debt is restructured.

In Ireland, it’s a very different picture. No riots, instead people have waited for the election to have their say. All major political parties ruled out any sovereign default. Even Sinn Féin, which is opposed to austerity measures (favouring instead increased taxation), had as part of its manifesto standing by Ireland’s self-imposed debts. The fringe left-wing United Left Alliance – and their position on sovereign debt is at worst ambiguous – only garnered 2.5% of the popular vote.

The typical Irish citizen may only be learning now the full extent to which the last three Governments increased permanent spending commitments on the back of temporary or fragile revenues. But the election shows clearly that Ireland’s citizens believe the country should not welch on debts honestly accrued, however painful that might be. This is because the price to be paid would be a poorer economy for their children.

(2) …but Ireland does not view banking debt as part of its sovereign debt

Only the two outgoing Government parties viewed Ireland’s banking liabilities as an integral part of its sovereign debt. All other parties – and most of the non-party candidates, such as the New Vision electoral alliance – campaigned on a platform of “burden-sharing” and/or renegotiation of the IMF-EU debt, i.e. that the collapse of Ireland’s financial system should have costs for more than just the Irish taxpayer.

The Irish people have overwhelmingly endorsed the latter view, with the outgoing Government parties taking less than one in every five votes cast. In other words, the new Government has been given a mandate based on the belief that tying banking debt to the Irish taxpayer is part of the problem, not part of the solution. With Irish bond yields at record highs, it seems the markets and the Irish electorate are in agreement on this. Only some EU-ECB elites seem out of step.

“I’ve been reading Krugman, Sachs and Joseph Stiglitz. And they all seem to be saying the same thing to me…”

As Clifford T Ward might have said… The solution is obvious. It’s not only obvious, it’s mostly good news for the EU and ECB. While it’s embarrassing for them, it’s not painful. They will have to admit that they were wrong to pump Irish banks to the hilt full of loans and deposits, long after the private sector had deserted the same institutions. But they can protect the bondholders and all it will cost them is giving the ESF loans to Ireland at no interest rate premium. This cuts the cost of banking debt in Ireland more or less in half, enough to convince the market the burden is manageable.

There is no moral hazard argument as the externality here – contagion in Europe’s financial system – does not apply to any of the Club Med economies, at least not in the same order of magnitude. Profligate economies cannot be rewarded with cheap loans – but the reason Ireland is in need of help from its neighbours is not its own profligacy. The reason Ireland is need of support is because the EU extended credit for a lost cause well beyond any measure of common sense. One of the clearest voices on this is Peter Mathews, who has just been elected as a representative for Fine Gael, which will lead government, and who is set to be a vital part of the team that will be sent to talk to European chiefs.

But – odd as this may sound to a global observer – there was a lot more to Ireland’s election than the global sovereign debt crisis. In fact, that was probably only the side show…

(3) Ireland’s underlying issues are nothing to do with bondholders or deficits

Firm statistical evidence of this will be hard to come by, but it is clear that what the Irish electorate is really smarting from is not austerity or the lack of burning bondholders. These have just lit the touchpaper on the two real issues facing Ireland: unemployment and negative equity. According the most recent official figures, 300,000 people are unemployed in Ireland, up from just 100,000 before the current economic crisis. While Ireland’s under-18s are lucky enough to be able to choose skills that are in demand, their older siblings are not so lucky. The burden of unemployment is falling on Ireland’s 20-somethings, with one third of men between 20 and 25 unemployed, and they are set to emigrate.

Things are hardly better for Ireland’s 30-somethings. At least 200,000 households – and maybe as many as 300,000 – are in negative equity. This is out of a total of 800,000 households with a mortgage. Just yesterday, the Central Bank published its latest mortgage arrears figures, including a new series on numbers of mortgages that have been restructured. All in, about 10% of mortgages are already in trouble.

The solution to both of these issues is of course not burning bondholders or austerity. It is what every politician seeks: jobs. Ireland has three engines of jobs growth: international demand, domestic investment and domestic consumption. Consumption and domestic sentiment is out for the count and won’t recover until the other sources deliver. Opportunities for domestic investment are few and far between, although a national retrofit program and schemes related to renewable energy may provide some boost.

The onus will fall on Ireland’s ability to compete internationally. Fortunately, Ireland is relatively well placed. It has consistently out-performed in attracting FDI jobs in the last three years. Its manufacturing sector – which was hardly affected by the collapse in trade at all – has just recorded its strongest performance in 11 years. With property costs about half of what they were five years ago, and with a general improvement in relative costs of the order of 10% on the rest of the eurozone, Ireland looks set to do so again over coming years. And who knows? Maybe NAMA’s “gift from history” of nearly-free accommodation for workers and firms may turn out to be a further shot in the arm for Ireland’s competitiveness.

John Mack ,

Would it make sense, in marketing excess housing, to start a “Buy Ireland – Bargain Prices” campaign aimed at Irish-Americans, and Europeans?

Stephen Hamilton ,

If the banking debts are to be written down or made more affordable with lower interest rates then should some of this saving not be used to help out those in negative equity by writing down unaffordable mortgages?

MichaelG ,

Ronan,

You say:

“…but Ireland does not view banking debt as part of its sovereign debt”

You then go on to say that reducing the interest premium to nil on the ESF loan is all that is necessary to make everything all-right for the Irish taxpayer and the Bondholders.

Is not the problem with the ESF loan that it is designed to cover our current Budget deficit over the next number of years while we have already raided our current cash reserves and the NPRF to “invest” in weak and failed Banks?

If we did not have the Banking/Building crisis we would not have taken on liabilities of €50-€100 billion and would have been able to workout the Budget Deficit by borrowing a similar amount on Bond-markets as to what has been borrowed from the ESF.

The issue remains that we settled 100% with the Bank Bondholders since the September 2008 guarantee whereas there should have been a negotiated settlement for something in the region of 30-50% face value. We did this at the insistence of the EU/ECB who in effect levied a tax on us.

The ECB should give us the ESF fund free with no repayment of interest or capital.

We have already paid enough towards solving this crisis!

FlyOver ,

John Mack said on March 1, 2011 | PermalinkWould it make sense, in marketing excess housing, to start a “Buy Ireland – Bargain Prices” campaign aimed at Irish-Americans, and Europeans?

This Irish-American is trying to find a bargain price in Ireland but have yet to find any!!! And to add, the Euro/dollar conversion and I feel I will be staying put here in Flyover country (Ohio) for some time to come.