Nobody knows at this juncture the scale of the losses for bank balance sheets from mortgage write-downs. But the EU-IMF deal had to set aside a certain amount for contingencies relating to future losses – including those from mortgages – and chose €25bn. This post attempts to shed some light on the potential scale of mortgage write-downs. Given that purpose, it almost completely sidesteps the broader economic and social impact of negative equity, arrears and repossession, not because these are not important topics, but because they are worth their own research, not as sidepoints in a discussion about bank balance sheets.

The Morgan Kelly question: three types of bank assets

Morgan Kelly has been the most vociferous on the apparent “time bomb” for banks in Ireland’s mortgage arrears. His estimates stem from his “realistic loss” scenario, published on the Irish Economy website in May, where he estimated that of €370bn in all lending by Irish banks, a figure that includes loans abroad, €106bn would be lost. In truth, his estimate is driven almost entirely by Irish bank lending within Ireland, so he is predicting bank losses of €100bn off a loan book of €235bn.

Based on these figures, he then wrote an article in early November, entitled “If you thought the bank bailout was bad, wait until the mortgage defaults hit home“. One could legitimately assume from this that if losses from loans that went to NAMA were bad, those from mortgage foreclosures would be worse. Indeed, this was the general conclusion: this is an article that spooked markets around the world. I know, as I was out of the country at the time and saw the immediate reaction from a non-Irish perspective.

Given that Morgan has been right on so much over the last five years, including his prediction in that very article that Ireland would need an EU-led loan, is there nothing to do now but brace ourselves for the mortgage arrears time bomb that will surely make the bank bailout look like peanuts? To shed some light, it’s worth thinking about three main types of bank asset and therefore three main types of potential losses: NAMA, arrears and SMEs.

- NAMA losses are losses from big property speculation. Irish banks lent out about €100bn in large chunks (i.e. typically more than €5m) for land and development which is now falling under NAMA’s remit.

- Arrears losses will stem from residential properties that the banks have to foreclose and sell for less than the mortgage outstanding. Total residential mortgage lending in Ireland stands at about €115bn.

- SME losses are where small businesses go under and banks have to take their place in the queue to get money out of the assets that are being liquidated. Corporate lending in Ireland stands at about another €100bn.

On the face of it then, it seems reasonable to say that if we’ve been focusing almost exclusively on the €100bn or so in NAMA-related lending, then the €100bn or so in mortgage lending is indeed an elephant in the room. (I will have to leave for the moment the issue of SME losses, both because I’m not an expert on that issue and because that was not the focus of Morgan’s article.) On NAMA losses, banks face somewhere in the region of €40bn of losses on NAMA-bound properties, in round numbers and allowing for past efforts at external recapitalisation.

Estimating the number of borrowers at risk

Is this €40bn in bank losses from land and development going to be small compared to the losses from bank balance sheets due to mortgage arrears? Suppose there are three types of people with mortgages: (1) new borrowers, with large debt which more than likely swamps their equity, (2) old borrowers, with small amounts of debt and (relatively) large amounts of equity in their homes, and (3) topper-uppers, who are probably in the main similar in profile to old borrowers. The risk category for banks is almost exclusively new borrowers, because it is unlikely that they will have to repossess the homes of old borrowers or of topper-uppers, and if they do, the equity in the house will very likely cover the debt.

So how many new borrowers are there? To be safe, we should assume that anyone who has borrowed since 2003 is at risk, whether they are first-time buyers or not, apart from topper-uppers. Why since 2003? If prices fall 55% by 2012 – which may just be enough to bring the rent-price ratio back to normality – prices will be back at levels seen in 2000, broadly speaking. This is about 20% below 2002 levels, so if someone who bought in 2002 had to sell in 2012, they could, as on average they will have paid off about 25% of the principal by then. By looking at quarterly IBF data, which go from 2005, and a similar Dept of the Environment series, it is possible to estimate there have been about 435,000 borrowers since 2003 who are either first-time buyers or mover-purchasers. This is out of a total of 800,000 mortgages.

In truth, given the loan-to-values and outstanding debt involved, it’s reasonable to think that 2003 and 2009 borrowers are of different types to their 2006 and 2007 counterparts. Using a combination of IBF, Dept of Environment and county-level Daft.ie data, it’s possible to estimate the number of households in negative equity. If house prices fall 55% from the peak, about 330,000 households would be in negative equity, compared to about 200,000 households now, including two thirds of all 2006-2007 borrowers and more than half of 2004, 2007 and 2008 borrowers.

But even then, we can’t just multiply 330,000 by, say, an average mortgage of €200,000 and assume that €65bn of the mortgage loan book is at risk. Many of those borrowers will remain employed and – perhaps grudgingly but consistently – pay off their mortgage each month. They may represent a threat to economic growth, as people feel less wealthy when their homes are worth less, but such households are not a threat to bank balance sheets.

Estimating how much of the loan book is at risk

Instead, we need to look at the proportion of negative equity households at risk of foreclosure, i.e. where circumstances such as unemployment lead not just to arrears and Court proceedings but ultimately foreclosure. The first step is to look at mortgages in arrears: there are currently 40,000, a figure that may rise to 100,000 in a pessimistic scenario. With an average mortgages of €200,000, this suggests that a maximum of €20bn of the mortgage loanbook is at risk.

Even then, the underlying asset, the house, will not have lost all its value. Very few properties would have only get half their loan-value back, the back of the envelope figure that Morgan uses. For this to be the case, the average borrower would have to have bought at the peak with a 100% interest-only mortgages. This is not the average – this is the upper bound. A more reasonable rule of thumb is that banks will recover two-thirds of loan value on average. So the upper bound in mortgage-related write-downs is now perhaps €7bn.

This figure still needs to be scaled down again, not just to reflect the fact that not everyone in arrears of less than 180 days progresses to deeper arrears, but also to reflect that not everyone in six months or more of arrears has their home repossessed. At the moment, about one in four mortgages in arrears goes from the 90-180 days category to the 180-days-plus category. This may rise to one half over time, as people run out of outside options, but I’m not sure anyone is actually going to predict anything like 50,000 mortgages having Court Proceedings issued.

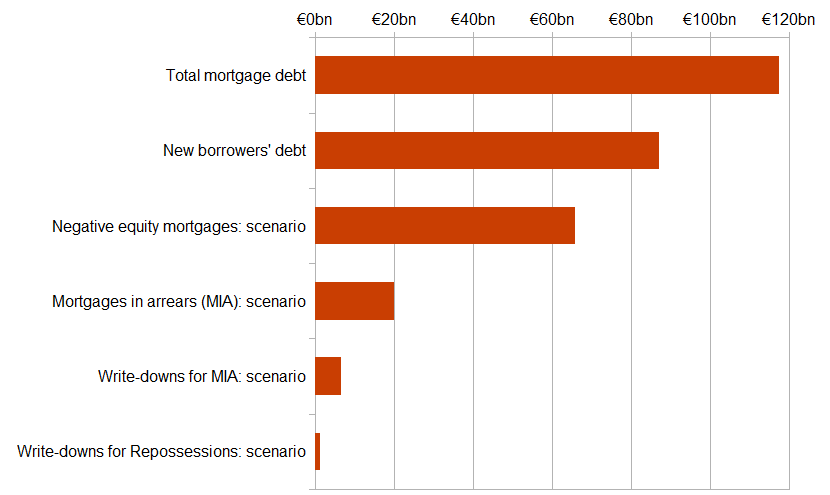

Currently, repossessions are running at a rate of about 300 a year. This will almost certainly rise as some of those currently scraping by fall victim to the ongoing recession and as the moratorium on repossession passes. But are we seriously expecting an average of 5,000 repossessions every year from 2011 to 2020? Suppose repossessions instead jump from 300 this year, to 1,500 next year, 5,000 in 2012 and 2013, and then falls back gradually to about 500 by 2020. That would be a calamitous scenario for all those affected. But what would it mean for the bank balance sheets? The graph below recaps the figures discussed in this post. The punchline is that repossession of 20,000 homes and their resale by banks for two-thirds of their loan value would mean balance sheet losses in the order of €1.3bn.

This is a far cry from claims that mortgage arrears will cast losses on banks that will make NAMA look like a sideshow. You could be three times as pessimistic about the number of repossessions and more cautious about final values and still struggle to get above €5bn in bank losses. You might even somehow be able to construct a case that I’m out by a factor of 10. But I struggle to see how someone could make the case that the figures above are out by a factor of 50, let alone 100.

Morgan’s article is full of depressing vistas: a “torrent of defaults”, a “social conflict on the scale of the Land War” and the rise of a “hard right, anti-Europe, anti-Traveller party”. Perhaps I am young and naive, or excessively fond of the Simpsons, but this reminds me of an exchange in the Simpsons, where TV host Kent Brockman asks his expert guest: “Hordes of panicky people seem to be evacuating the town for some unknown reason. Professor, without knowing precisely what the danger is, would you say it’s time for our viewers to crack each other’s heads open and feast on the goo inside?” To which the Professor responds: “Mmm, yes I would, Kent.”

That is perhaps the point. By basing his predictions for losses on the idea of 200,000 mortgages hitting the wall, Morgan is making a social prediction – i.e. that people will lose faith in society and all hell will break loose – not an economic one. He may yet be right, but if all social fabric is rent asunder, then probably most economic bets are off.

FERGUS O'ROURKE ,

Would you actually go so far as to say that “Professor Kelly is Wrong” Or am I to be forever burdened with the copyright on that ? 🙂

See http://bit.ly/9rD8hL

Ronan Lyons ,

Hi Fergus,

I’ll leave you with that one if I can copyright the comparison with the egghead in the Simpsons!

I’ve been discussing this with a few other economists, and I think it’s fair to outline here some of the factors that for reasons of brevity didn’t make it into what was already a very long blog post. There are very few answers for these points, but they do have to enter the calculus:

First, are banks only at risk from recent non-top-up borrowers?

Secondly, I more or less just picked a number for mortgages in arrears out of nowhere, 100,000 compared to 40,000 now. What will affect the number of mortgages going from negative equity to formal arrears?

Thirdly, how will mortgages in arrears convert into foreclosures and at what price?

Feel free to add to these factors below.

R

Joseph ,

Surely there is a real threat that interest rates will rise sooner and faster than you are suggesting Ronan? There must be a ‘tipping point’ where those going into arrears accelerates. This added on to increasing outlays over the next couple of years and I still don’t believe the cost of living in Ireland is getting any lower despite what official figures may say.

It’s hard to believe that countries like Germany won’t need a hike in rates next year and a bit of inflation to boot.

Ronan Lyons ,

Hi Joseph,

Thanks for the comment. In truth, it’s difficult to say what will happen interest rates. As soon as one or two countries start demanding an increase to cool their economies, while others need low rates, the days of a relatively harmonious ECB will presumably be gone. Given the incredibly precarious state of the markets, though, it’s difficult to see interest rates going up before 2012.

It’s difficult to even say how much of the market this affects. It seems from some newspaper reports that there are about 150,000 tracker mortgages. A 92% 35-year mortgage on a property bought for €200,000 currently on 2.5% pays €1,060 a month. If ECB rates went as high as 4%, meaning a tracker rate of 5.5%, this would mean a mortgage repayment of €1,625. It is indeed difficult to see how the typical household could afford €600 more a month on their mortgage.

R

Arthur Doohan ,

Greetings Ronan.

With an economist’s hat on, I think your assumptions are on the ‘fair to optimistic’ end of the spectrum and the medium term analysis is reasonable, logical and measured.

But…

With my trader’s hat on, I have to say that your major assumption is that of ‘normal medium term’ outcomes applied to a crisis.

Globally, we have already had one complete market liquidity lockout. Globally, we are all on emergency liquidity assistance and are still only moments away from another market ‘seizure’.

At such moments, medium term averages become meaningless and current cash flow determines everything.

And the cashflow of the Irish mortgage holder is very weak, indeed.

Ronan Lyons ,

Hi Arthur,

Thanks for that very fair comment and reminder about the importance of cashflow. Both your comment and Joseph’s refer to the non-linearities involved, which is a very important point. 300 repossessions from 30,000 arrears almost certainly doesn’t scale up neatly to become 3,000 repossessions from 300,000 arrears. What does it scale up to, though? My attempt here is to say, even with 30,000 repossessions (so 10% repossession, not 1%), this is still not NAMA all over again for the banks.

The social costs are, of course, another issue entirely.

Anonymous ,

[…] […]

Clive ,

Hi Ronan,

A very interesting analysis. Could i ask you if you were to guess how much further a fall in % terms do you see the Dublin properry market dropping. And what would be the likely timescale for such adjustments. I ask this because we are considering stepping into the market.

Thanks

Clive

Paul Mara ,

Hi Ronan

I see Minister for Finance Brian Lenihan is noted as having a similar view on a mortgage meltdown as you do. It is reported here:

http://www.breakingnews.ie/ireland/lenihan-not-worried-about-potential-mortgage-meltdown-485618.html

It looks like his point is that mortgage defaults are related to unemployment and that unemployment has stabilised.

I was wondering if you have any further (maybe follow-up) opinions on this matter?

Thanks

Paul

Phil Doyle ,

I think the analysis is very thorough but optimistic. There is a real risk of shorter term rate rises as banks are funded at increasingly higher rates of interest. We’ve already been a 0.5% rise in rates charged to retail mortgage customers.

A significant rate rise to home owners would place many more people in arrears and could lead to far greater bank problems.

Property values have declined hugely and therefore realisable housing asset values are low so repossessed properties would not yield more than 50% of purchase price if bought in the last 6-7 years.

Finally, Lenihan believes that unemployment has stabilised. Employment is not rising therefore a static unemployment figure is being achieved either by emigration or fudging of stats or both.

Arthur Doohan ,

Greetings Ronan.

I have a side-question for you.

Is there a property index time-series available in the public domain for download / modelling anywhere?

For the RoI – nationally would do, regional/sectoral would be great….

regards

AD

John O'Dea ,

Ronan,

As someone who lent about €1B in the height of the boom to various types of borrowers, I can assure you, you are way out. The loss provisions the banks are likely to put away are in the order of 15-20% of the book. Kelly may be painting an apocalyptic scenario but you are definately painting a rosie one. Anything from €10B to €20B will go down the pan on this one….. With the moratorium on reposessions (from both a legal and a pragmatic point of view) the current figures are only the thin end of the wedge. It’s somewhere between what you have predicted and he has. Not the end of the world as we know it, but very very ugly nonetheless.

John

The Irish Economy » Blog Archive » Hump-Shaped Dynamics ,

[…] for who can come up with the biggest number for the banks losses, it is worth taking a look at Ronan Lyons’ analysis of potential mortgage-related […]

Al ,

Hi Ronan

Should wage levels, etc, settle down to y2000 levels along with house prices, people who got into mortgage difficulty will be still compromised.

Further should Croke park be looked at again, how many people will be closer to the danger zone.

There may be enough room in the eye of the needle for the country to get through all this, but is it going to screw mortgage holders along the way?

I think Morgans thoughts on this referred to those in the danger zone getting organised politically, with the whole situation getting ugly etc.

ivor belkin ,

Ronan,

Might not your fair to optimistic view might earn you a McLoughlinesque reputation – calling a soft landing for mortgage defaults? Why leave the BTL elephant outside the room with its 28bn in debt much of which was financed throuugh “equity” release loans off PDH? Consider the bankig capital requirement on 145bn in mortgage debt much of which is carrying +100% LTV’s – reckon this LGD exposure is c€80bn.

Ivor

TC ,

Ronan

If you look at the formulae in the spreadsheet at the Irish Economy posting in May, you will see that Morgan Kelly’s “optimistic” estimate of the loss on mortgages across all lenders is 5% of the €82 billion domestic mortgages book, or €4 billion. He puts his “realistic” estimate at 10% or €8 billion.

Jake Watts ,

How does it look from the bridge of the Titanic? The ten year bond is back up to 8.5% and Moody’s just downgraded five nothces. And, you talk about 2.5% money for 35 years? Also, who is going to buy the houses when they come on the market? With every emigrant, you surely just lost a home buyer. Why not factor in a sovereign default on the return to the mean senario?

Jake Watts ,

Why does Ireland not take the cash from the IMF and the ECB at 5.6% and buy its own ten year bonds at 8.4% and live off the spread like US banks?

Jake Watts ,

My comments have been awaiting “moderation” for a day. Either accept them or come out as a censor.

Daniel ,

Ronan,

I really appreciated reading your analysis and opinion. I have no professional expertise in this field, but from a basic point of view, how likely is it that prices would stabilise at 2000 levels (as you said “broadly speaking”)? In 2000, was there not inward investment?, was employment not rising? was there not a shortage of housing? were we not just joining into the single currency? was money not becoming more accessible for everyone? I’m not one for nostalgia, but it certainly felt like the future was much brighter for Ireland and the Irish in 2000 as opposed to 2010. I would have thought this prognosis was also supported by national balance sheets as well as sentiment. Are we not facing into large scale contraction (the effects of the recent budget have yet to be felt) over the next few years with less and less spending money and borrowing power on an individual and national lever? I know this is probably oversimplified demand supply economics, but what is the probability of prices stabilising at 2000 levels? There would appear to be an abundance of empty and unfinished housing and even rented housing in most main towns around the country with receivers and others still deciding what to do with it. I hope for all our sakes that my pessimism is misplaced. You comments would be appreciated. Thanks again for all your work and analysis. Daniel

John ,

thanks for your insights. good blog. Much change is needed, and drastic changes too. Hopefully sooner than later.

Billy O'Mahony ,

Hi Ronan,

Given the current talk about trackers I remembered this thread and thought I’d get some info on the size of the tracker losses here.

But your figures do not (I think) address the on-going losses that the banks are suffering on their tracker mortgages. If there are 150k tracker with on average 200k outstanding and the spread between what the banks are sourcing funds at versus what they are charging the mortgage holder is 4%, that equates to 1.2bn losses p.a. on the back of my envelope.

Not too bad relative to the entire bank bailout but significant in terms of the 10bn on mortgage losses you talk about here.

Can you enlighten us any further on this issue?

Thanks.

Ronan Lyons ,

Hi Billy,

As noted in my first comments above, you are right and this does not specifically estimate losses from trackers mortgages. The Sunday Times had an estimate of the cost of trackers to PTSB, which came to €400m a year (IIRC), although this will fall slightly when the gap between Irish bank financing rates and the ECB rate declines over coming years.

The reason I focused purely on repossessions and losses therefrom was that this article was in response to Morgan Kelly’s predictions purely about that topic – I hope that makes sense.

Thanks for the comment,

Ronan.