Earlier this month, amid a reasonable amount of fanfare, the World Economic Forum launched its latest Global Competitveness Report. Given its name, this report, and its IMD counterpart, the World Competitiveness Yearbook, are staples for most policymakers and marketeers involved in foreign direct investment. Think of the typical economic development official, talking to a room of suited corporate executives and pointing to a nice chart where his country is heading in the right direction and you get the picture. Better yet, read China’s response to the latest report and you’ll see exactly what I mean.

However, what is competitiveness? And how can it be measured? And what’s the best measure out there? Ireland’s National Competitiveness Council has a framework for understanding competitiveness, its essential conditions and its policy inputs (see, for example, page 19 of their annual report). In it, competitiveness is framed as just a means to another means (sustainable economic growth), which hopefully contributes to the end, i.e. better standards of living for a nation’s people.

The World Economic Forum attempts to measure competitiveness by looking at a range of areas, with twelve separate pillars in three main sections, from basic requirements such as institutions and infrastructure, through efficiency enhancers (e.g. higher education, technological readiness) to innovation and sophistication factors. A lot of thought has clearly gone in to how the index is structured. The most important thing to remember, though, is a model’s use in the real world is only as good as the data that go into it. And, having identified the important factors, and seeing that most of them lack official hard data, the WEF’s solution is to survey executive opinion in each country.

This is, of course, a significant improvement on having no data at all. Such a survey, however, has limitations, limitations that are all too often forgotten in the clamour for parliamentary questions explaining a fall of two places in the latest rankings. Firstly, sample sizes may not be that big, particularly in small countries and/or those with not a lot of big business. Secondly, these are not the same people being asked year-in, year-out. Thirdly, it’s not the same people being asked to rate different countries. Put more mundanely, all questions are on a scale from 1 to 7. Across individuals, let alone across cultures and continents, someone’s seven might be someone else’s six. Lastly, because it’s opinion, it can be influenced by sentiment even if framework conditions are actually going the other way.

So, what’s the solution: throw up our hands and say competitiveness can’t be measured? No. The WEF rankings are useful, once the limitations are known about. Secondly, the people giving the scores are often decision-makers, so their opinions do matter when it comes to competitiveness and location foreign investment in one region or another.

Another recommendation would be to take a leaf out of the World Bank’s book and, instead of asking businessmen, do the unthinkable and ask some lawyers! What have lawyers got to do with competitiveness? Well, they can tell you how many procedures have to be filled out to do x or y, for example hiring workers or applying to be connected to utilities. And the World Bank’s Doing Business rankings do just that. They go through the lifecycle of a business, from starting a business and dealing with construction permits to getting credit, paying taxes and trading across borders. All the measures underpinning the score are hard data (or indices based on hard data), for example the number of procedures required to register property or the cost of importing a container.

What does a comparison of the two tell us about international competitiveness?

- Executives’ high opinion of Switzerland is not matched by actual data. It comes first in the WEF index, but 21st in the Doing Business rankings. In terms of setting up a business, Switzerland is outside the top 70 in the world, a fall of almost 20 places in the last year. Its lack of transparency of transactions means it has one of the worst scores in the world for ‘Protecting Investors’, while there are twice as many tax payments to be made in Switzerland compared to the OECD average.

- Executive opinion might be a good proxy for large changes, albeit slightly lagged. The poster-country for reforming its ease of doing business last year, Azerbaijan (which ranks 38th in Doing Business) saw its rank improve significantly in the WEF index this year, up 18 places from 69th to 51st.

- The WEF survey may give countries false cause for concern. Ireland, for example, saw its rank stay steady at 7th this year in Doing Business, but its WEF ranking is much further down and falling, down to 25th this year from 22nd last year. What this should say to the policymaker is not that it is getting more difficult to do business in Ireland, but that executive sentiment thinks more poorly of Ireland – something that requires an entirely different response.

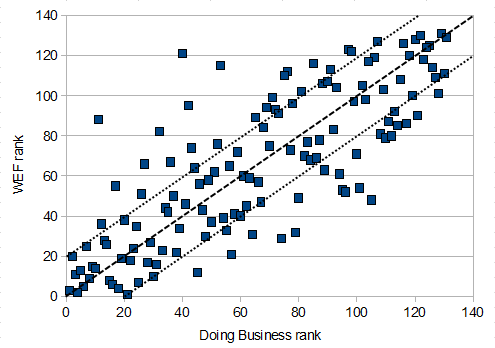

The graph below shows a scatter of the 130 or so countries in both rankings. The correlation between the two is reasonable but far from perfect. Only one third of countries have a similar ranking in both (similar meaning less than 10 places away). Quite a lot of countries are outside the dashed lines, i.e. more than 20 rankings away.

It is of course entirely fair to state that the WEF measure is a broader one as it tries to capture everything from education to e-readiness. That, however, is also its challenge for policymakers – no government can overturn generations of under-investment in schools or technology over night. Plus it’s somewhat ‘motherhood and apple pie’: what government is not investing in those areas?

The Doing Business rankings tell a broadly similar story, in terms of who ranks where, but due to their nature, they can do it with much greater precision and a much greater imperative for action by policymakers. A business lobby group, for example, reading the report in Russia can point to the number of days or procedures required to export or connect to utilities or get a construction permit and, looking at rapid improvements in neighbours such Azerbaijan as Georgia, reasonably ask why not here too?

Lawyers 1, Businessmen 0!

Fergus O'Rourke ,

My door is always open 🙂 Davos can be “cool”, I hear

Reforming taxes on work the big challenge to EU competitiveness | Ronan Lyons ,

[…] statistics, which are based on countable, real-world processes and which are, in that respect, a much better set of figures to give to policymakers worried about competitiveness than better known but more abstract […]

The importance of ease of doing business for economic recovery: evidence from 1,200 new jobs | Ronan Lyons ,

[…] week, the World Bank Doing Business rankings for 2011 were released. These rankings are, in my opinion, the best direct measure of the competitiveness of one country’s business environment. The […]