About 10 years ago, two French economists compiled a database of international inequality, François Bourguignon of the World Bank and Christian Morrisson, of the University of Paris. The database gives estimates of population, GDP per capita and the percentage of national income going to each decile of the population, with the top 10% of the population broken into two 5% intervals. These figures together can be used to calculate approximate GDP per capita of various parts of society, from the poorest 10% to the wealthiest 5%.

Their resulting paper based on these figures was published in the American Economic Review in 2002. Their analysis showed that world inequality worsened from the early 19th century to World War II and after that stabilized – or at least grew more slowly. They also spot an interesting difference. In the early 19th century most inequality was due to differences within countries; later, it was due to differences between countries.

Rawlsian philosophy, as outlined in John Rawls’ Theory of Justice, suggests that we should think in terms of ‘original position’. That is to say, when one wants to evaluate a policy, principle or program for justice, one should act as if:

no one knows his place in society, his class position or social status, nor does anyone know his fortune in the distribution of natural assets and abilities, his intelligence, strength, and the like. I shall even assume that the parties do not know their conceptions of the good or their special psychological propensities. The principles of justice are chosen behind a veil of ignorance.

The practical implications are that a society must consider its least well off citizens. Taken to an extreme, one could throw out all conventional measures of success, economic or otherwise, and replace it with one simple measure – how well off is the least well off person in society?

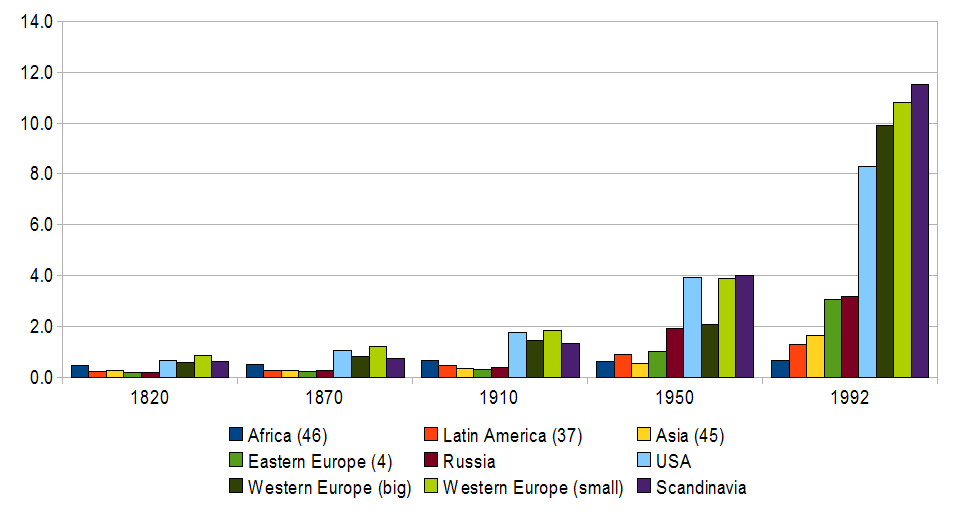

Bourguignon and Morrisson’s data allow a compilation of a Rawlsian measure of economic development – namely the GDP per capita of the poorest 10% of a society. The chart below shows the number of 1992 US$ per day enjoyed by the bottom 10% around the world between 1820 and 1992. Among the world’s region’s poorest 10% are the $1-a-day population, the focus of the Millennium Development goals. Getting them to two dollars a day is regarded as the bare minimum required to get them out of extreme poverty. The regions covered, which are representative rather than exhaustive, are ordered in how well off the poorest 10% were in 1992. The data for Africa, Asia and Latin America are very comprehensive, although there are caveats about the quality of the pre-1950 data generally and the pre-1890 data in particular.

As you can see, even by 1910, the poorest in every region in the world still had not passed $2 a day. Only by 1950, and even then with some exceptions, had Western Europe and its offshoots (somewhat lazily represented here by the USA) reached a level of comfort in all levels of society.

Interestingly, Russia – during its USSR experience – did achieve one of the goals of its the socialist philosophy, bringing a decent standard of living to its poorest, an achievement achieved also in Eastern Europe, particularly post-1950. Latin America, which has a history of inequality, did bring its poorest citizens greater prosperity than Asia, until the 1960s. Since then, however, it seems Asia’s economic growth has been broadly based and the 25% gap in relative prosperity that its poorest citizens suffered relative to Latin America has swung the other way. Nonetheless, the poorest of both continents still enjoyed an average income of less than $2 a day in 1992, compared to $3 in the ex-Soviet Bloc and $10 in the “First World”.

The biggest story of these figures has to be Africa, however. Its status as a ‘failed continent’ is well known but what surprised me was its loss of relative position. Far from always being the poorest continent, its poorest citizens were – up to World War 1 – the best off in the world outside Western Europe and its offshoots. The two generations between 1910 and 1960 saw Africa go from ‘best of the rest’ to the poorest of the poor.

Even worse, not only was its progress in the 1960s the worst of all regions – both Latin America and Asia broke through the $1-a-day for their poorest citizens during this decade – between 1970 and 1992, the continent regressed, particularly during the 1980s. Almost a century of stasis from 1910 to 1992 has meant that Africa’s poorest are still on three quarters of a dollar a day, just as they were in the 1910s.

From a Rawlsian perspective, the persistence of poverty and the plight of Africa is not just tragic, it verges on the baffling, given the edge Africa had in relation to poverty on other developing regions up to the Great War.

Stephen.kinsella@gma ,

Hi Ronan, best thing by Bourginon et al is this book, the microeconomics of income distribution. I know one of it’s authors, can send you some slides on his idea of generalised income distributions. Would *love* to do this for Ireland in a short paper, even have the maths done. Check it out: http://tinyurl.com/mhzuvb)