Education – what economists call human capital – is probably one of the most important determinants of well-being. A newly available dataset gives researchers the means to test a range of fundamental hypotheses, such as the link between education and fertility, democracy and inequality. The dataset is by Morrisson and Murtin and is described in their paper, “The century of education“, which is being published in the Journal of Human Capital this year.

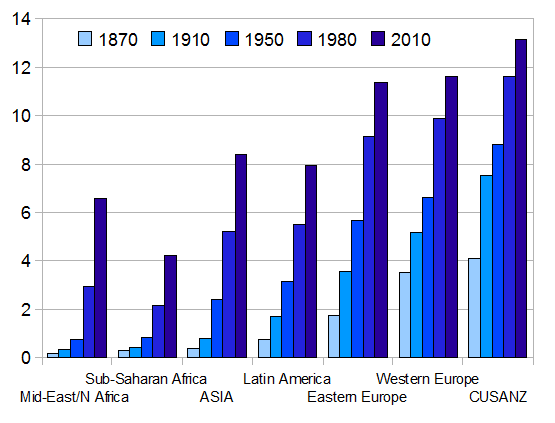

Their dataset uses a variety of techniques to build a consistent set of figures across over 70 countries every ten years from 1870, the start of heightened globalization pre-WW1, to 2010. In addition to the ‘usual suspects’ (i.e. the OECD), the dataset has good coverage in Africa and Latin America but relatively poor coverage in Eastern Europe and Asia. The top level finding is that there has been a continuous spread of education that has accelerated in the second half of the twentieth century. The authors find fast convergence in education across advanced countries during the 1870-1914 globalization period and evidence of modest convergence since 1980, but in both cases, less developed countries have been “excluded from the convergence club”. Less developed countries are improving, but they are not necessarily catching up yet. An overview of average years of schooling by region is presented below.

As you can see, regional rankings haven’t changed over time that much – apart from the Middle East and North Africa overtaking Sub-Saharan Africa between 1950 and 1980 and Asia overtaking Latin America between 1980 and 2010. (CUSANZ, incidentally, comprises Canada, the USA, Australia and New Zealand, also known as the Anglo-Saxon offshoots.)

Already, a number of papers have been released that use the dataset – which is freely available for all to download – to tackle key hypotheses or theories about economic development. For example, people say the world is getting more unequal and that this is due to globalization, given that we live in a globalized world. But it is impossible to attribute causality that way, particularly if the world is also becoming more education at different speeds, more industrialized or more democratic. Greater inequality in terms of education, industrialization or democracy may instead explain any rising inequality. The two authors combine the education dataset with another dataset on inequality, built by Morrisson and Francois Bourguignon, to examine the relationship between education and inequality. They find that average education has been the key determinant of income inequality over the past century.

Other papers by Murtin examine the relationship between education and fertility and between education and democracy. He finds that education again is the most robust explanation of the fall in fertility that occurs during economic development and that education (in particular primary schooling) has been at least partly to explain for the emergence of democracy since 1870.

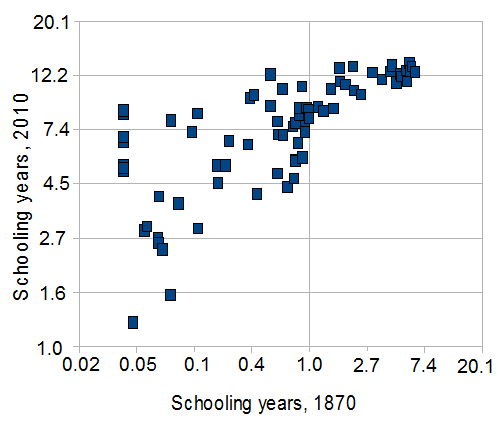

These are optimistic findings. After all, education, unlike for example geography, is more susceptible to policy influence. To stem inequality and high population growth rates and to promote democracy, education is key. One potential downside is that education, at least in terms of rankings – i.e. a country’s place in the pecking global order – is sticky, as the graph above shows. Regions that are behind find it difficult to catch up. Fortunately, country-level data give a slightly more optimistic picture. The graph below shows a scatter of education in 1870 with education levels now. It is shown in log scale.

Education ranking is indeed sticky, but mostly at the upper level. Those countries that were in the top 10 in 1870 were very likely to still be there in 2010. However, there were a variety of experiences for those countries with less than a year’s schooling on average in 1870. Some had very little more by 2010, others had up to 12 years average schooling. This shows that something – presumably policy or at least influenced by policy – can have an impact on a country’s relative position.

Datasets like these are economists’ versions of ‘standing on the shoulders of giants’. As researchers build and improve these datasets, they free up other economists to use and analyze the data.

Leave a comment